Artists and the Law: Exploring A Jurisprudence Of New Capabilities

December 24, 2013 12:00 am Leave your thoughts

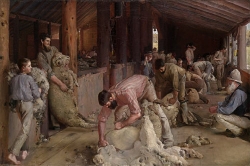

When I first heard the suggestion that the judiciary and greater Parliamentary oversight could ‘save the day’ and redress the reckless use of new capabilities by Britain’s security service GCHQ, an image flashed into my mind of a 1903 painting by Australian impressionist Tom Roberts – known locally as The Big Picture. It records, historically and artistically, the first Parliament in Australia. Or in American filmic terms, the Birth of A Nation. Given that I am an Australian artist this seems natural to me, but I know that if creative thinking was currently accepted into the chronological argumentation of legal logic then my point would be less unorthodox. Despite all our talk of innovation, unorthodox perspectives don’t get across so simply.

It has been suggested by Australian constitutional historian Helen Irving that this and other Australian impressionist painters helped Australians to imagine their political system into existence – albeit using an older continents system of law. The experience of The Heidelberg School painters in late 19th century Australia is an apt metaphor for how creative thinking, our imagination and a legal system co-create each other.

When faced with increasingly advancing technology and new capabilities, this point seems important to revisit. Especially when what is legal and what is criminal is getting blurred. I sit on the side that believes that our legal structures, its language and logic, is unable to adapt to the changing narratives which rely more and more on what is possible, rather that what has actually been created. The current reaction to these legal and ethical ‘blank spaces’ is the concept of the ‘pre-emptive’, which has proven a damaging concept in international relations. As in the past, art and politics bears many lessons for today.

In 2011 Australian Parliament House Director of Art Services Kylie Scroope wrote a paper that raised 2 points that I want to discuss in relation to how the UK Parliament debates how security services respond to new capabilities. Scroope notes that Robert’s colleague artist Arthur Streeton observed in the federalist journal Commonwealth how our Federation was unconsciously created by artists and galleries. At the same time Irving writes of the period that “‘the people of the states first had to imagine the idea of a nation called Australia, before that nation could exist. [and that the] process of imagining the country into existence occurred at a number of levels.”. ‘

And while it is acknowledged that both Australian impressionism and the Australian Constitution was “‘very much about promoting allegiance to a vision of a dominant, white, British culture;'”, I can still learn how a creative lens helped construct or initiate a new political reality. This history seems worthy of revision by British lawmakers before throwing the security services into the jaws of a judicial review that still frames unknown and changing realities as illogical realities.

I am suggesting that a ‘jurisprudence of new capabilities’ is needed to address this gap. That is, a new philosophical grounding and conceptual framework of the law which nails down what cyberspace actually is, how we see ourselves as citizens within and outside it, and how science and technology alters the physics of how we understand space, time, motivation, opportunity, threat and harm itself. Contemporary jurisprudence doesn’t value how imagination transforms new technologies into threats and benefits. These include conceptual spaces and wording which allow for metal to return to a previous form under extreme heat; or bacteria and viruses to be as affective in making new fuels and medicine as much as promoting harm.

It is doubtful if a broad debate about how surveillance capabilities balance security and privacy will question implicit assumptions within the law when under pressure to assuage a concerned public. The purpose of this blog is to raise these issues as necessary for inclusion in such a debate. Also to position creatives and legal practitioners as unlikely allies in this debate at a time when human resources of creativity are flourishing in Britain.

One of the bigger issues that this collaboration could explore is how equipped governmental and judicial processes are to describe and govern the next wave of new technologies. It is clear that current laws lack the ability to describe evolving technological capabilities. Robert’s Big Picture almost completely revoked the innovative lens he used to paint his 1890 painting Shearing The Rams. In the story of his paintings lies the lesson that to incremenatally transplant one continent of thinking into another is worthwhile while risking opportunity. The opportunity to think more creatively, to go beyond what we know, is laden with fear and insecurity. Legal reasoning does not allow for imagination’s role, but government’s historical capacity for adopting and selling new ideas can lead in ways that our current judiciary cannot.

If we apply legal reasoning to new technological problems without equally new conceptual tools, we are depending on a hermeneutic tradition grounded in outdated texts; and on the grey area of interpretivism by individuals who may – or may not – understand the science and sociology of change. Most likely they would be trained out of using imagination to meet imaginative threats. They need certainty to make a judgement, I understand, but if uncertainty defines the present, we need to question the assumptions within any ‘pure’ logic of reasoned analysis and argumentation before re-authoring our future through legislation.

Legal precedent also excels more at evoking the narratives of the past than at writing the stories of the future, including understanding the role of automation and artificial intelligence in decision making. The hermeneutical tradition we use make assumptions of the way that time and space affect crime and punishment. Freedom and injustice has changed beyond recognition for many, and remain a puzzle for millions who do not interact online. But if these laws can agree on a concept of mutability which make the values of the past relevant to how we imagine the future, then current laws may help governments strike a balance between security and privacy without promoting new forms of legal positivism that actually restrict our security services ability to respond to new threats. Again, without a jurisprudence that appreciates the role of new technologies this will not occur.

Artists are comfortable with both certainty and uncertainty – but understand the choice. I don’t see this awareness in lawmakers today because it has been written out of their tool book. A jurisprudence of new capabilities would be an active act of creation rather than an unconscious re-action. Such legislation could only be retrospective.

In painting we have the issue of background and foreground, and as painters we experience anxiety at the importance of choosing which, when and where to position them. That is where a jurisprudence of new capabilities can help in shaping debate. For law and creativity to collaborate takes risks on both sides. Like two cultures from different continents meeting on the shores of a new land – weapons at hand – art historians still argue hotly if the bland governmentality of The Big Picture is what sapped Roberts of his creative passion – or if it gave him the common sense to give up on commercial success and just enjoy painting.

Engaging with legal structures can make artists risk shattering their unique lens. To lose sight of the value of their strategic unreasonableness. Yet the lack of certainty of new technologies demand that we step out of the safety of our traditional thinking in order to meet non-traditional problems with an open mind.

This article first appeared on http://www.carlgopal.com/article/?185 and is reprinted here with kind permission from the author

Tags: ArtsCategorised in: Article

This post was written by Carl Gopalkrishnan