Smuggling Music and Sex Education: ‘Bravo’ Magazine in the German Democratic Republic

September 5, 2008 12:00 am Leave your thoughts Where there is prohibition, a vacuum is filled with a black market. On the long list of prohibited items in the former German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, the most sought-after contraband for young people was not Coca Cola, clothes or David Hasselhof (contrary to what he might think) but

Where there is prohibition, a vacuum is filled with a black market. On the long list of prohibited items in the former German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, the most sought-after contraband for young people was not Coca Cola, clothes or David Hasselhof (contrary to what he might think) but

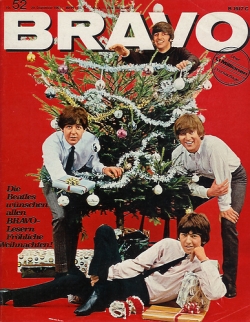

copies of Bravo magazine, the German cult rag for young people. Its coverage of music, film and television stars, (and Hasselhof here has to be grudgingly included) as well as its handling of teen issues, made it a highly-coveted black market commodity.

The Bravo phenomenon

Calling itself a tabloid that unashamedly targets the teen market, this muted definition of Bravo belies its prominent role in providing generations of Germans with a frank sex education. Many credit the magazine, at least in part, for Germany’s free and uninhibited attitudes towards sex and the body. The magazine was founded 1956 (with Marilyn Monroe gracing the maiden cover) at a time when post-War Germany wanted to emerge from its misery and embrace modern life. Since 1962, it has given no-holds-barred advice on sex and growing up through the advice of “Dr Sommer”, resident agony uncle and real-life doctor (though Dr Sommer is a pseudonym). Generations of Germans and other Europeans in this way received their Aufklaeurung (‘clearing up’) on matters of sex.

Bravo of course is also a celebrity gossip mag. Teenagers learn about the lives and loves of America’s biggest stars along as well as the best method of contraception for young couples. Amusingly, unlike its British counterparts, (heat for example) it never pokes fun, tongue-in-cheek or otherwise, at the people it covers. Every also-ran gets treated like they are the next Elvis Presley – from international superstars like Michael Jackson to German pop runts Tokio Hotel and some of Central Europe’s most embarrassing “dance acts”- DJ Bobo and DJ Oetzi, take note. This

affectionate strategy does seem to pay off, however. It should be noted that Bravo followed boy band ‘N Sync’s fortunes like a swooning teenager (its key demographic) from the mid-1990s, when they could barely fill school gyms in Germany and Austria and Justin Timberlake had yet to grow

facial hair.

Despite its importance, Bravo manages to completely avoid political issues, with the exception of the environment and animal rights – issues that are deemed important to its target audience. Its most politically daring acts to date: printing a picture of Pope John Paul II and publishing stars’

thoughts on America, post-11th September 2001.

Smuggling Bravo

Thanks to its whole-hearted celebration of Western celebrity, the Bravo was banned in the GDR, not for its sexual content but because it was labelled an example of ‘decadent Western thought’ and ‘imperialist literature’ by the Committee for Entertainment Arts. But for young people in the GDR, it formed a vital connection to the world beyond the wall because of its voyeuristic coverage of music and film stars. More than that, it was a link to the stranger world of growing up and sex, its frank treatment of which children in the West may have taken for granted.

An article in the Berliner Zeitung in 2006, marking Bravo’s 50th Anniversary, discusses the smuggling of the magazines into the GDR. One teenager used to travel to Hungary with her friends to loot the music shops for albums banned under the GDR, as well as editions of Bravo. Another girl

paid the equivalent of 20 DM (£8) for the latest issue – it would have set her back about 1.70 DM had she lived on the right side of the iron curtain.

Despite its status as culturally bankrupt and unfit for GDR eyes, Bravo was thoroughly catalogued, archived and rated. Possession of Bravo was strictly prohibited, which is why it was often smuggled on 18-hour train rides from Hungary, under sweatshirts against bare skin, at the mule’s annoyance upon finding the cover illegible by the sweat. Often it would have to be peeled from the belly. For West Germans, who could pick them up while buying toiletries, this may sound somehow romantic.

Along the borders and in the post offices, the government did its best to stop the influx of Western literature, but some Bravos managed to slip through. Covert trade of Bravo’s colourful posters in GDR schools was so brisk that it even had fixed prices: A double-sided poster went for 20

Ostmarks, a single page poster for ten. The larger posters could fetch up to 40 marks and a whole magazine would cost 100. This was at a time when young apprentices in the East earned only 120 Ostmarks per month, and children’s pocket money was not usually more than 20 marks a month.

Somehow, the money was always there.

Most people brought Bravo to the GDR when returning from visits, but because the eager customs goons would search luggage, smugglers had to be inventive. Sasha Lange, in his book “DJ West Radio – My Happy GDR Youth” recounts how his mother, when returning from the West to visit his

grandmother, would go to the toilet just before she went through the checkpoint, and hide various papers and magazines in her boots. Another magazine would go under her sweater.

There was further money to be made in the photographs taken of Bravo pages, again with fixed prices: “These became so valuable that they were given out as prizes at the Leipzig fun fair shooting gallery. I once won a picture of Kim Wilde, but because I was such a bad shot, I spent five marks on ammunition,” says Lange.

Lange says that the obsessive collection of posters among schoolchildren surpassed the collection of music records. Finding a poster which you wanted required making use of every contact you had, inside and outside school, to find out who had something you wanted and who might want something you had. “I had a grandmother in the West – this is how I managed to get my hands on over 80 posters of Depeche Mode,” says Lange.

Black market music

Bravo also helped people in East Germany place words and faces to the music from ‘over there’. Claudia Rusch writes in her 2003 book, My Free German Youth, that music was more difficult to censure than literature. If a book was banned, it was simply not imported. End of story. “Music was different. As soon as Western songs were played on the West’s radios and people walked down the street singing them, it was too late. They settled like fine dust on the ears of people in the GDR,” says Rusch. The furtive and urgent collection of Bravo, with its voyeurism of music stars and colourful posters, was part of this vicarous consumption of Western music, and sated

some of the hunger for banned music.

For the music-hungry in the GDR, every titbit contained in Bravo’s pages was considered sacred. “Everyone knows the anecdotes,” Rusch writes. “The black market, the false covers of Bohemian horn music, and of course the Bravo posters, which could cost up to a month’s salary.”

Every song that contained the word “free” became a cult hit in the GDR. Rusch laments that Bob Dylan could not have known the true importance of his 1987 concert in East Berlin, and how disappointing it was for his music-starved audience that he said almost nothing during his performance: “Like it was just another one more point on a long list of irritating

obligations – but for the people there, it was like seeing God.”

Still here and not forgotten

Antje Pfeffer of the Youth Archives Project in Berlin, says that presumably the yearning for the music-and sex-education paper was nowhere stronger than in the GDR. The Archives Project documented the German history of the magazine to accompany its 50th anniversary celebrations. Pfeffer herself

grew up in the GDR, and does not recall any smuggling of Bravo but remembers other curious behaviour. She has fond memories of a black and white picture of Rory Gallagher a childhood friend photographed from his copy of Bravo and then sent on to her. The Archives museum is full of such

grainy, overexposed and secretly developed snapshots of Bravo stars and articles.

The subject of Bravo within the GDR was also examined by the magazine itself. In 1967 it published letters from girls from sent from ‘over there,’ assuring them their names and addresses would not be printed. The letters described how they were approached by middlemen, who offered 12

marks per page and 60 DM for a whole edition.

Of course, there was nothing comparable at the time. Nowadays Bravo is one of many youth magazines, its copycat versions, Popcorn, Pop Rocky and Girl skimming its profits and diluting its circulation. In days past, whoever wanted to have posters of Western stars could not avoid Bravo. Perhaps another reason to be nostalgic for the Cold War: Bravo is now available everywhere but is nowhere near as coveted.

Categorised in: Article

This post was written by Alexa Van Sickle