WHATEVER HAPPENED TO ‘MY GENERATION’?

April 8, 2017 12:00 am Leave your thoughts If the young and only the young were allowed a vote we would be living in a very different society. It would bear some resemblance to the world we once thought would come into being. There’d be no filthy rich and no dirt poor. There’d be Penguin Specials [and I don’t mean chocolate bars] everywhere, and there’d be just a few under-the-counter Daily Mails. Management Studies would be teaching workers how to take control. The high rise towers of the City would never have disgraced the skyline. Certain broadcast media would know their place.

If the young and only the young were allowed a vote we would be living in a very different society. It would bear some resemblance to the world we once thought would come into being. There’d be no filthy rich and no dirt poor. There’d be Penguin Specials [and I don’t mean chocolate bars] everywhere, and there’d be just a few under-the-counter Daily Mails. Management Studies would be teaching workers how to take control. The high rise towers of the City would never have disgraced the skyline. Certain broadcast media would know their place.

Dream on. It isn’t like that. And there are those who ask, ‘Whatever happened to the idealism of my generation?’ Anyone who remembers the Sixties/Seventies years finds themselves asking that question in a variety of moods ranging from confusion to resignation to fear to rage. Of course it is every generation’s later experience to discover maturity certainly tempers idealism. People eventually negotiate terms with society’s conventions. The revolution that never was becomes the social democracy that nearly was and just might be in the future.

It’s a natural and healthy process to channel ideals into practical effects.

What is unhealthy is the hardening of hearts and narrowing of minds by the cynicism, selfishness and greed that governance from the hard right has consciously encouraged for years. But it’s no use blaming everything on some political abstraction. Current attitudes were willed into being with the support of electors who now surely are fully aware of what they are doing, but don’t care as long as they remain secure.

That has to be the conclusion. It’s a bitter truth to accept, but acceptance seems inescapable, although the lasting bitterness resides within the tide of reaction.

These reactionary attitudes may be human nature, but they are only a part [among the worst parts] of human nature. There is an altruism and idealism that can be appealed to and that can be encouraged. The tradition of such encouragement has a long history. Some may trace it back to the Enlightenment or to Renaissance humanism. Others may go further back to ethical positions of religious teachers and humane philosophers since Antiquity. In modern times the development of an acknowledged social responsibility has been a serious advance in civilization.

Reaction, of course, has been a recurring threat. Jackboots and barbed wire are the obvious manifestations. So, too, with the charlatans and chancers who exploit revolutionary dreams. But there are subtler forms of reaction that encroach on the humane progress of society.

Half a century has passed since John Fowles spoke of an ’emotional quasi-liberalism’ associated with cultural modernity, but which is not in itself progressive in any fundamental sense. I first read those words not fifty years ago, but some time since. And they continue to serve as a warning, or even [if I am honest] an admonition. Let’s put it like this: wearing scruffy jeans won’t feed the hungry. Vague feelings are not deeply-held convictions.

A poem of Peter Porter’s, John Marston Advises Anger, compares the Jacobean theatre [and society] of Marston to the then contemporary Swinging London. A Mad World, My Masters does have strikingly modern resonances four centuries on. Porter sees the Sixties as essentially a change of style rather than substance. The note of caution remained so relevant to my generation coming alive in the Seventies. The relevance is indeed continuing.

I am not John Marston, nor do I advise anger. There was much to learn in the counter-culture and its successor movements, like Occupy, for example. There is no need to counsel despair while the lights of resistance and of hope burn.

But to speak of the idealism of a generation is to ascribe a single pattern of feeling and action to a variety of experiences. The more thoughtful and the more achieving may be described in a certain way. Yet within that description there are those whose sympathies were qualified by their future conduct. There were student radicals who became Blairite ministers. Some of their contemporaries never really shared the experiences, or at least not with much depth of feeling. Then, as now, there were many young whose priorities centred on their personal lives and ambitions. Apathy and careerism shadowed ‘the idealism of my generation’. In the end the shadow prevailed.

Nostalgia sees things differently. The right does not have a monopoly in sentimental remembrance. Nostalgia will give the romanticized version of the past.

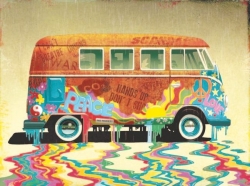

Photographs of Haight-Ashbury in the Summer of Love show young people looking casual but not as strikingly different as they seemed at the time. That is not how it is remembered. It is not how it could be portrayed. A dramatic recreation would need to exaggerate for effect the way things looked then. What began as a challenge was to become a convention. Society absorbs the challenges that do not change it.

There are other nostalgias. There is a sentimental tear shed for a sense of community that ignores the petty jealousies and corrosive gossip that are inherent in close-knit groups. There are those who dream of empire again, not in reconquered colonies but in terms of trade, national standing and military might. These nostalgias soon reveal their obstructive nature. We cannot move forward by looking back. A sense of history is one thing [an essential thing], but false memory dwells in the realm of wishful-thinking. What is needed is a clear view of how things actually are. And that is not easy to find among the competing myths which seek to persuade the future into being.

There may be no agreed descriptions of social reality. The right-wing ascendancy speaks in patriotic language that refers back to a popular history of national sovereignty.

The prevailing social morality is a notion of the free citizen acting only in self-interest. It is justified as liberty, a liberty supposedly chartered in age-old custom and of beneficence to all who pledge loyalty to the mystique of Britannia. .

Social democracy cannot identify any existing society within this imperial myth. The transnational nature of an evolving European society naturally works toward a European Social Union working for international peace, rather than a fragmented continent of belligerent states. Progressive union is the possibility from which a mythic reaction withdraws. The project is not the radical utopia of our dreams, but it will evolve as capital accumulation is forsaken in favour of a socially responsible economic model. That is probably the only available reality.

A credible ideal is there for those who wish to have a future that works.

Categorised in: Article

This post was written by Geoffrey Heptonstall