Crusaders and Zionists

October 10, 2014 11:34 pm Leave your thoughts

Lately, the words “Crusaders” and “Zionists” have been appearing more and more often as twins. In a documentary about ISIS I just saw, they appeared together in almost every sentence uttered by the Islamist fighters, including teenagers.

Some sixty years ago I wrote an article whose title was just that: “Crusaders and Zionists”. Perhaps it was the first on that subject.

It raised a lot of opposition. At the time, it was a Zionist article of faith that no such similarity existed, tut-tut-tut. Unlike the Crusaders, the Jews are a nation. Unlike the Crusaders, who were barbarians compared to the civilized Muslims of their time, Zionists are technically superior. Unlike the Crusaders, the Zionists relied on their own manual labor. (That was before the Six-Day War, of course.)

I have already told the story several times of my attachment to the Crusaders’ history, but I can’t resist the temptation to tell it again.

During the 1948 war my commando unit was fighting in the South. When the war ended, a narrow strip of land along the Mediterranean Sea remained in Egyptian hands. We called it the “Gaza Strip” and built outposts around it.

A few years later, I read Steven Runciman’s monumental “A History of the Crusades”. My attention was immediately drawn to a curious coincidence: after the First Crusade, a strip of territory along the sea was left in the hands of the Egyptians, extending a few kilometers beyond Gaza. The Crusaders built a string of fortifications to contain it. They were in almost the same places as our own outposts.

When I finished reading the three volumes, I did something I never did before or since: I wrote a letter to the author. After praising the work, I asked: Did you ever think about the similarity between them and us?

The answer arrived within days. Not only did he think about it, Runciman wrote, but he thought about it all the time. Indeed, he wanted to subtitle the book “A guide for the Zionists on how not to do it”. However, he added, “my Jewish friends advised against it.” If I ever chanced to pass through London, he added, he would be glad if I called on him.

I happened to be in London a few months later and called him. He asked me to come over immediately.

(The name Runciman was familiar to me: his father, Walter, a viscount, was sent by Neville Chamberlain in 1938 to mediate between Nazi Germany and the Czechs, and scandalized the world by greeting the Germans with “Heil Hitler”.)

Steven Runciman answered the bell himself, a tall British gentleman of about fifty. Being an incurable anglophile, I was enchanted by his courteous aristocratic manner.

After a glass of sherry, we sank into a discussion of the Crusader-Zionist parallel, and lost all sense of time. For hours we compared events and names. Who was the Crusader Herzl (Pope Urban), who the Crusader Ben-Gurion? (Godfrey? Baldwin?), who the Zionist Reynald of Chatillon (Moshe Dayan), who the Israeli Raymond of Tripoli, who advocated peace with the Muslims? (Runciman graciously pointed to me).

Years later, Runciman invited my wife and me to Scotland, where he had moved to live in an old watchtower near Lockerbie, built as a defense against England. Over dinner served by a lone manservant he spoke about the ghosts haunting the place. Rachel and I were astonished when we realized that he really believed in them.

The two historical movements were separated by at least six centuries, and their political, social, cultural and military backgrounds are, of course, totally different. But some similarities are evident.

Both the Crusaders and the Zionists (as well as the Philistines before them) invaded Palestine from the West. They lived with their backs to the sea and Europe, facing the Muslim-Arab world. They lived in permanent war.

At the time, Jews identified with the Arabs. The horrible massacres of the Jewish communities along the Rhine committed by some Crusaders on their way to the Holy Land are deeply imprinted in Jewish consciousness.

Upon conquering Jerusalem, the Crusaders committed another heinous crime by slaughtering all Muslim and Jewish inhabitants, men women and children, wading “to their knees in blood”, as a Christian chronicler put it.

Haifa, one of the last towns to fall to the Crusaders, was fiercely defended by its Jewish inhabitants, fighting shoulder to shoulder with the Muslim garrison.

I was brought up hating the Crusaders, but I was not conscious of the abysmal hatred Muslims felt for them until I asked the Arab-Israeli writer Emil Habibi to sign a manifesto for an Israeli-Palestinian partnership over Jerusalem. In it, I had listed all the cultures that had in the past enriched the city. When Habibi saw that I had included the Crusaders, he refused to sign. “They were a bunch of murderers!” he exclaimed. I had to omit them.

When Arabs couple us with the Crusaders, they clearly want to say that we, too, are foreign intruders, strangers to this country and this region.

That’s why the comparison is so dangerous. If the Arabs entertain such a deep hatred for the Crusaders after six centuries, how are they ever to become reconciled with us?

Instead of wasting our time on the debate about whether we are similar or not, we would be well advised to learn from the Crusaders’ history.

The first lesson concerns the question of identity. Who are we? Are we Europeans facing a hostile region? Are we “a wall against Asiatic barbarism”, as Theodor Herzl proclaimed? Are we “a villa in the jungle”, according to the famous dictum of Ehud Barak?

In short, do we see ourselves as belonging to this region or as Europeans who accidentally landed on the wrong continent?

To my mind, this is the basic question of Zionism, going back to its first day, and dictating everything they have done to this very day. In my booklet “War or Peace in the Semitic Region”, which I published on the eve of the 1948 war, I posed this question in the very first sentence.

For the Crusaders, this was not a question at all. They were the flower of European knighthood and they came to fight the Saracens. They made Hudnas (truces) with Arab rulers, mainly the emirs of Damascus, but fighting Islam was their very raison d’etre. The few advocates of peace and reconciliation, like the aforementioned Raymond of Tripoli, were despised outsiders.

Israel is in a similar situation. True, we never admit that we want war, it is always the Arabs who refuse peace. But from its first day, the State of Israel has refused to fix its borders, being ever ready for expansion by force – exactly like the Crusaders. Today, 66 years after the founding of our state, more than half of the daily news in our media concerns the war with the Arabs, inside and outside Israel. (Last week, our Minister of Agriculture, Ya’ir Shamir, demanded that we take urgent measures to limit the birthrate of the Bedouins in the Negev – like Pharaoh in the biblical story.)

Israel suffers from a deep-seated sense of existential insecurity, which finds its expression in myriad forms. Since Israel is in many ways a conspicuous success story and a world-class military power, this sense of insecurity often gives rise to wonderment. I believe that its root is this feeling of not belonging to the region in which we live, of being a villa in the jungle, which really means being a fortified ghetto in the region.

It could be said that this feeling is natural, since most Israelis are of European descent. But that is not true. 20% of Israeli citizens are Arabs. At least half of the Jews have come here (they or their parents) from Arab countries, where they spoke Arabic and listened to Arab music. The greatest Sephardi thinker, Moses Maimonides (Rambam in Hebrew) spoke and wrote Arabic and was the personal physician of the great Salah ad-Din (Saladin). He was as much an Arab Jew as Baruch Spinoza was a Portuguese Jew and Moses Mendelssohn a German Jew.

Were the Crusaders a small aristocratic minority in their state, as Zionist historians always contend? Depends on how you count.

When the first Crusaders arrived in Palestine, the majority of the population was still Christian of various Eastern sects. However, the Catholic invaders did look upon them as inferior strangers. The Poulains, as they were called, were despised and discriminated against. They felt themselves closer to the Arabs than to the hated “Franks”, and did not mourn when these were finally ejected. Most of these Christians later converted to Islam, and were the forefathers of many of today’s Muslim Palestinians.

Another lesson is to treat immigration seriously. In Crusader society, there was a constant coming and going. Just now, a flaming debate about immigration is going on in Israel. Young people, mostly well educated, with their children, are leaving for Berlin and other European and American cities. Every year, Israelis look anxiously at the balance sheet: how many were driven to Israel by anti-Semitism, how many were driven by war and right-wing extremism back to Europe? This was a tragedy for the Crusaders.

One main reason for the Zionist rejection of the Crusader parallel is their sorry end. After almost 200 years in Palestine, with many ups and downs, the last Crusaders were literally thrown into the sea from the jetty of Acre. As the former underground chief and prime minister, Yitzhak Shamir, the father of Ya’ir, was fond of saying: “The sea is the same sea and the Arabs are the same Arabs.”

Of course, the Crusaders had no nuclear bombs and no German submarines.

When ISIS and other Arabs use the term Crusaders, they do not mean only the medieval invaders. They mean all American and European Christians. When they speak about Zionists, they mean all Jewish Israelis, and often all Jews.

I believe that this coupling of the two terms is extremely dangerous for us. I am not afraid of ISIS’ military capabilities, which are negligible, but of the power of their ideas. No American bomber is going to eradicate these.

It is getting late. We must de-couple ourselves from the Crusaders, ancient and modern. 132 years after the arrival of the first modern Zionists in Palestine, it is high time for us to define ourselves as we really are: a new nation born in this country, belonging to this region, natural allies of its struggle for freedom.

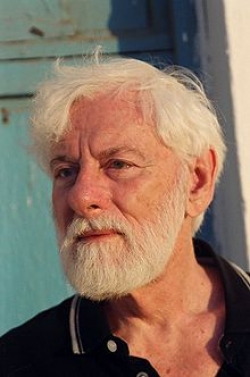

Uri Avnery is an Israeli journalist, co-founder of Gush Shalom, and a former member of the Knesset

This article first appeared on the website of Gush Shalom (Peace Bloc)- an Israeli based peace organisation

http://zope.gush-shalom.org/home/en/channels/avnery/1412954246/

Tags: Middle-EastCategorised in: Article

This post was written by Uri Avnery