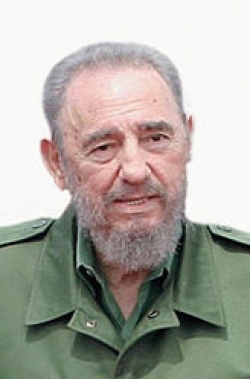

Book Review: “My Life” by Fidel Castro

January 18, 2008 12:00 am Leave your thoughts Fidel Castro’s memoir shares a title with Bill Clinton’s autobiography of 2004. But those who picked up the latter in the hope of reading the juicy stuff about Monica Lewinsky will be similarly disappointed if they skim Castro’s version for gossip about Che Guevara’s illegitimate children or the details of Castro’s 638 (and counting) assassination attempts. This is a lengthy conversation between two book covers, in question-and-answer form and lumped into titles like “Bay of Pigs,” “Summing up a life and a revolution,” and “Cuba and Neoliberal Globalisation.”

Fidel Castro’s memoir shares a title with Bill Clinton’s autobiography of 2004. But those who picked up the latter in the hope of reading the juicy stuff about Monica Lewinsky will be similarly disappointed if they skim Castro’s version for gossip about Che Guevara’s illegitimate children or the details of Castro’s 638 (and counting) assassination attempts. This is a lengthy conversation between two book covers, in question-and-answer form and lumped into titles like “Bay of Pigs,” “Summing up a life and a revolution,” and “Cuba and Neoliberal Globalisation.”

Ignazio Ramonet, Castro’s biographer and conversational sparring partner, has been criticized for not confronting Castro about some aspects of his regime, but this was never meant to be a judgement of Castro’s Cuba: these are Castro’s memoirs. He had the final cut, and as such it should be viewed as the version of history that Castro wants people to read; he edited it from his sickbed in 2006.

As he says himself: “People know more or less the entire history of Rome, or what is said to the the history of Rome, because history is full of anecdotes,” so this volume should be seen as precisely that.

Cuba’s history is furnished with plenty of fact but it is also opaque- there has been deliberate muddying of the waters on both sides of the Florida Strait. Castro himself is finely balanced between relic and icon, hero and tyrant, and Ramonet hopes this book will “lift the veil from the Castro enigma.” We are left with the distinct impression that Castro might not want this. There is very little about his private relationships and the minutiae of a life that might make him more accessible. What remains, then, is to sort the fact from the spin: to the world of fact belong the successes of the Revolution in the fields of education and healthcare; literacy and life expectancy are among the highest in the world.

It is also a fact that Cuba has been subject to a relentless campaign of biological attacks, psychological warfare and a disastrous economic blockade that nobody in the United Nations supports- with the notable exceptions of the US, Israel, Palau, and the Marshall Islands. One can only imagine what would have happened if Cuba had any oil. Through the last four decades, Castro has managed to make nine US presidents look foolish, and this is currency in Latin America. In the region where the US has meddled, with disastrous results, in the affairs of Mexico, Chile, Panama, and Nicaragua, it is no wonder that he is admired for his cojones if not for his politics.

The chapters covering his childhood and earlier struggles seem, at worst, like one of his long-winded four-hour speeches, but it is well worth raking the coals to find the embers. There are a good deal of historical gems here, ripe for the picking in this era of Cold War nostalgia. Espionage, propoganda, lies- and that’s just the Nixon administration, who spread the rumour that children in Cuba were being shipped off to the Soviet Union to be turned into tinned meat. Castro has also included letters sent between himself and Kruschchev during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, and even a letter he sent (which went unanswered) to Saddam Hussein warning him against invading Kuwait.

Some of Castro’s longest answers are in response to Ramonet’s (and indeed the reader’s) questions about the treatment of human rights and political prisoners in Cuba. You can only admire his politician’s treatment of them, but his defences of the humanitarian credentials of his regime don’t always ring true- just this week, people were arrested for giving out copies of the Declaration of Human Rights in Havana.

Evaluating him or his regime is beside the point. People are not of merit to the study of history for their ethics- quite the opposite, in fact. Call it a reserve of the true leader or an individual who likes the sound of his own voice, but he is articulate, well-informed and passionate, which are not qualities found in abundance in today’s politicians. Though he can be pompous and convoluted in his speech at face value, his talent for speeches is converted into good prose. Of course, he may be the last of a type- and for this reason alone the book is an important historical anecdote. Which brings us to the most burning question- summed up in Ramonet and Castros’s final conversation; “After Fidel, what?” A lengthy response is boiled down only to: “I will stay as long as I believe myself to be useful. Not a minute less, or a second more.” (I don’t think I have given away the ending).

Categorised in: Article

This post was written by Alexa Van Sickle