Lies, Damned Lies and Opinion Polls

January 30, 2012 10:53 am Leave your thoughts I was born in May 1947. In only the first four years of my life was there a Labour government that made a fundamental and lasting difference to the life of the nation. Subsequent administrations have certainly contributed to the lives of various groupings, but almost entirely in the realm of social policy. And none of these achievements – the Open University, say, or civil partnerships – is unimaginable under a relatively enlightened Tory government. What is more, many of the most far-reaching measures – reform of the divorce and abortion laws and abolition of the death penalty, for instance – have only prevailed through the stamina and determination of backbenchers introducing Private Members’ Bills.

I was born in May 1947. In only the first four years of my life was there a Labour government that made a fundamental and lasting difference to the life of the nation. Subsequent administrations have certainly contributed to the lives of various groupings, but almost entirely in the realm of social policy. And none of these achievements – the Open University, say, or civil partnerships – is unimaginable under a relatively enlightened Tory government. What is more, many of the most far-reaching measures – reform of the divorce and abortion laws and abolition of the death penalty, for instance – have only prevailed through the stamina and determination of backbenchers introducing Private Members’ Bills.

Both Clement Attlee and Harold Wilson invoked Lenin’s phrase about the need to take over “the commanding heights of the economy”. Attlee achieved more by that measure than did Wilson. In 2008, when the Brown government began to take significant stakes in high street banks, I dared to think that this dream might come to pass after all. But the imperturbable city easily frightens ministers with patently empty but apparently convincing talk of the need to remain independent, as with sophistry about attracting “the best”. Someone who will only work for a salary to which is attached a seven-figure bonus is not interested in service, only in self-service. Personal greed is not some kind of measure of financial acumen. In any case, under a global financial crisis, how can any self-important trader be sure that there are jobs elsewhere ripe for the picking? The city plays many bluffs that need to be given short shrift.

When it is being “pragmatic” – a favourite term of Wilson’s that was taken up by Cameron – Labour offers merely a less economically competent alternative, to which voters turn only when the Tories are exhausted and corrupt (1964, 1997). But Labour must present itself as creative, energetic and fearless. Ahead of the last televised debate of the general election, I wrote to Gordon Brown, recalling the catalogue of Labour’s achievements that he had presented to conference some 18 months earlier; it brought the hall to its feet. I vainly urged him to rerun the list in his television peroration. I still argue that Labour needs to think positively about what it has done; but even more so about what more it must do.

Governments of both left and right tend to move towards a consensual centre, thereby alienating their grassroots. Labour leaders shrug off the cries of betrayal. Wilson argued that Labour was always “broad church”. Jim Callaghan remarked that “you can never reach the promised land. You can march towards it”.

Such positions rationalise those governmental experiences that Rab Butler dubbed “the art of the possible”. Only in the unusually non-conformist climate of the immediate post-war years did a Labour cabinet feel sufficiently confident to implement a truly radical and reformist programme. That Attlee’s majority fell from 146 seats to a mere five at the subsequent general election suggests that these measures were unpopular. In fact, the 1950 election produced a bizarre distribution of spoils, for Labour actually increased its vote share on 1945. At a further election eighteen months later, Churchill was returned to power despite Labour winning a greater share of the vote than the Tories, its highest ever indeed. (This anomaly is explained by the Liberals recording their lowest ever share of the vote). Labour was then out of office for 13 years.

The most cogent criticism of the Labour opposition under Ed Miliband is that it is being too timid. Nobody makes cracks about “Red Ed” these days. I have plenty of proposals for radical policies that would get Labour elected with a comfortable majority. But a programme for government may wait until nearer the end of this parliament. We are not yet two years into the government by coalition and an opposition’s job at this juncture is roundly to oppose. This is a role that Miliband and his team have played with no more than fitful effect. A major part of the failure concerns the Labour front bench’s willingness to let Cameron make the running, score points at will (I know little of sport so I may be mixing some metaphors here) and persuade large swathes of the electorate to believe that all the pain being applied with such relish by the Tories (and such discomfort by the Liberal Democrats) is really the fault of Labour.

Cameron may be intending to fight the next general election on the record of the Brown rather than of his own administration. This would be a curious and probably unprecedented circumstance but shadow ministers have done all they may to encourage him in any belief that such a strategy might pay dividends. During the financial crisis of 2008-09, of which Brown’s handling won great credit from leading economists around the world, the Tory opposition scorned Labour’s wholly justified position that the crisis was global in nature. Needless to say, the present government blames world conditions – in particular those within the Eurozone – for the current slide in to recession, along with “the mess” that Labour bequeathed. It refuses to accept any responsibility for its own actions, which, thus far, have only achieved an increase rather than a cut in the deficit but deep cuts in the welfare state, along with a systematic preparation of both the NHS and the primary, secondary and higher education networks for wholesale privatisation. These things, we are regularly told, are “necessary”.

Labour seems to have decided to roll over and submit to this lamentable catalogue of abnegation of public responsibility. All it appears prepared to argue is for a temporary cut in VAT, the reduction of some bankers’ bonuses and some kind of unspecified revenge for the incidence of phone-hacking by journalists. The rest of Labour’s stance may be entirely embraced as temporising. There is undeniably a logic to this attitude, given that Miliband and Balls have effectively conceded that the last government “got it wrong” in almost every particular, which must infuriate Brown, Alistair Darling and indeed David Miliband.

Labour even seems incapable of negating the childish thrust, regularly rehearsed by coalition members and journalists alike, that Ed Miliband “knifed his brother in the back”. At the time of the autumn party conferences, Andrew Neil jovially suggested to Harriet Harman that Ed would never live this down. She ought to have had the wit to ask whether he would be putting to a leading Tory that Cameron back-stabbed David Davis. Because Labour is incapable of rebutting this canard, Cameron can rouse his backbenchers and the commentariat to orgasms of joy and admiration merely by rebuffing Miliband’s attempt to prise Cameron and Clegg apart with the line “it’s not like we’re brothers”. Is it beyond the wit of Labour’s scriptwriters to work up a new riff on the “two Davids” legend, this time with one strutting on the world stage and the other glowering among the also-rans? At least Ed invited his brother to serve. Cameron has put Davis out to grass.

I see that among “Executive Director” posts recently advertised by the Labour Party were those for Communications and for Rebuttal and Policy. We must hope that energetic and imaginative people were appointed. If nothing else, the job of rebuttal needs boldly ratchetting up with immediate effect.

Some significant opportunities have already been missed and will not come again. One was Libya.I doubt that there was deep public support for the government’s involvement in the Libyan civil war. Miliband had been opposed to the invasion of Iraq. He could have convincingly and consistently forged and led a parliamentary opposition to this enterprise, woundingly characterising it as Cameron’s amour propre and putting daily and unyielding pressure on the government to come clean about the true financial cost of the operation. Of course Cameron would have crowed about the fall of Gaddafi and made out that this “proved” that Labour was “wrong on this as on every other issue”, but such triumphalism is only ever temporary (as George W. Bush foolishly claimed one month into the Iraq debacle: “job done”) and we now see the regime in Libya both threatened by a newly resurgent rump and accused of being as brutal as its hated predecessor. Such sagas are never “over”. There may yet be more costs to the Treasury.

Labour says that it will accept the government’s cuts, even those that hit Labour’s heartlands hardest. “Being responsible” they call it. This kind of stance has become the norm for Labour ever since Harold Wilson’s day. In ancient times, one of the methods whereby you could confidently arbitrate between Labour and Tory was how the two parties approached issues such as state aid, tax rates, NHS availability, immigration and so on. There was a handy rule of thumb: Labour took the view that if a few people got relief who had no need of it, that was a price worth paying for ensuring that those who were in need were helped; the Conservatives took the view that if a few people who needed relief failed to receive it, that was a price worth paying for ensuring that public funds did not go to waste. It is no longer possible to chart this philosophical difference between the two parties. Labour and the Tories only diverge on the level of aid to be denied. Otherwise, modern Labour subscribes to the tabloid scapegoating of “benefit cheats” just as much as Tories do.

What governments can afford is always more about politics than about economics. Instead of joining in the psychology and language of “cuts”, Labour should come at it from the vantage point of imagining a clean sheet and then start to pencil in what it would spend. Looked at from that perspective, it is much easier to espouse, for instance, a policy that does not allow for tax avoidance, instead of the much more fraught exercise of trying to erode a status quo of sharp practice and finagling.

It is a puzzlement that, over its last 13 years in power, Labour never managed to close the many loopholes in the taxation system that allow those who can afford smart accountants to avoid paying their dues. Cameron takes the line that he needn’t make any reforms that Labour failed to make because Miliband has no grounds for complaint. Miliband can scotch that at once; two wrongs don’t make a right; even though it wasn’t done then, it must be done now. Tax avoidance is a major industry in Britain, but even without starting again with tax law it should not be beyond the wit of either Treasury or HMRC number-crunchers to scale it down significantly, if not eradicate it altogether. But Labour could begin by determining that the very profession of accountancy, the raison d’être of which is the avoidance of tax, be itself taxed as the luxury of the rich. Then we might be getting some place.

A method of avoiding tax much favoured by the mega-rich is the practise of dissembling in the matter of where one lives. The issue of “non doms”, that greatly exercised politicians and commentators on all sides a year or two ago, has dropped off the agenda in favour of high earnings. But moving one’s tax base – or the threat of doing so – remains a ploy for the powerful. The question of whether someone who lives abroad for tax purposes should enjoy status privileges in Britain is, to my mind, an irrelevant and misleading question. Where someone designates her or his principal residence is far too manipulable a matter. After all, the proprietor of The Daily Mail lives to all intents and purposes in Wiltshire but, by some sleight of hand, pays tax as a resident of Paris at a much more favourable rate than do run-of-the-mill Wiltshire multi-millionaires. Those who bear the onerous task of owning The Daily Telegraph from their tax exile in Monaco must laugh to scorn the fainthearted level of graft in the Westminster village, as so comprehensively uncovered by their organ. Moat-cleaning indeed! Why not acquire a Channel Island? That’s a vastly more cost-effective scam.

The problem of non doms is readily solved. Income should be taxed not on the basis of where the earner lives but where the income is earned. Better yet, follow the practice of the IRS in the US: tax without reference to either the location of the earner’s domicile or the country of the income’s origin. To avoid taxation, Americans have to renounce their US citizenship and even after that their US income is taxed on the same basis as that of a guest worker. If Americans can live with such a system, Brits sure as hell can too.

Perhaps there would be a degree of permanent departure from these shores among those unwilling to submit to contributing an appropriate proportion of their wealth to public provision. Such people merit a one-word response: “Goodbye”. If, to continue owning several mansions and a private jet, they are obliged to be based in a country where, beyond their gated communities, they are surrounded by abject poverty, that is for their consciences to reconcile. But it is a self-serving myth that our industries cannot survive without greedy, grasping individuals. They can and will survive (the BBC appears to have recovered from the departure of Jonathan Ross, for instance) because there are always people who are thoughtful as well as talented, who want work that is stimulating first and lucrative only as may be, and who will choose to stay in a decent society that diligently cares for all its members. Let those perpared to live abroad for tax purposes lose their right to British citizenship altogether. That would sort the merely greedy from the downright criminal.

Starting again from scratch on public spending, Labour would soon find many causes that do not merit support from the public purse. Such an exercise would readily release the funds that would be required for an equable welfare state and a properly financed state system for health, education, policing and local services.

Of course there are risks in pursuing such policies. The press barons (non doms all) will hit back through their newspapers. But that is a bridge that Miliband has already burned. For half a century, party leaders who made themselves amenable to Fleet Street, even if only by bestowing knighthoods, have received a largely favourable press: Wilson, Thatcher, Blair, Cameron. Those who paid less attention to the press – Douglas Home, Heath, Callaghan, Foot, Kinnock, Major, Hague, Duncan Smith, Brown – were increasingly pilloried. In this dynamic, Rupert Murdoch was the chief instigator and the others dutifully followed. In declaring war on News International, Miliband has ensured that the press generally will be hostile. There is much for the Executive Director for Rebuttal to do.

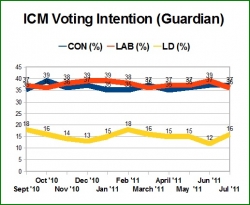

On one matter, the press is primed to make life difficult for leaders who suffer a particular sort of misfortune – and Miliband presently suffers it. It is a negative finding by opinion polls. I have long argued that polling organisations offer an utterly misleading pseudo-science that suits – and may very well be tailored to suit – the newspapers that carry their “findings”. On one of the slowest of news days, Boxing Day last year, The Guardian gleefully trumpeted an ICM poll that allowed it to headline its first leader, with almost indecent relish: “Cameron in command”. The paper was rewarded with days and days of name-checks across the media. A month later, ICM furnished it with figures that gave the Tories a clear lead. That day’s leader was stern: “Rogue polls are very rare. Most polls currently put the Tories ahead ‘ the polls are broadly right. And today’s poll is right. Better get used to it”.

Well, let’s just see. How many thousands of people were interviewed by ICM’s cold-callers? Oh right: 1,003. That is around 0.002 per cent of the UK electorate. How much certainty would you be prepared to erect on such minuscule foundations? Ah, but ICM (as do all polling organisations) has anticipated that. “Data were weighted to the profile of all adults aged 18+ (including non telephone owning households). Data were weighted by sex, age, social class, household tenure, work status and region. Targets for the weighted data were derived from the National Readership survey, a random probability survey comprising 36,000 [that’s 0.08 per cent of the UK electorate] random face-to-face interviews conducted annually. The data were further weighted by declared votes in the 2010 general election”.

In other words, the data that ICM gathers from this tiny sample of people who happened to answer the phone is not presented as is but is massaged by a process that is not disclosed. In a dictatorship, one imagines, the figures would be massaged by a combination of bribery and threat from the regime. Obviously that doesn’t happen in Britain but we are entitled to be sceptical of any undisclosed system of presenting data that is used for propaganda purposes. And then there is a factor that cannot be weighted, even by experienced masseurs: what percentage of respondents may be trusted to tell the truth?

“Rogue polls are very rare”. Oh yeah? Notoriously, the polls misforecast the outcome of the 1992 general election, even up to the BBC exit poll conducted on the day as voters were leaving the booths. Lots of rogues there. And I recall the 2004 US elections. I was staying with a friend and unable to sit up all night with the results as is my wont. Eccentrically, my friend (a BBC woman) had switched to ITV’s coverage and we heard the famous MORI pollster Robert Worcester tell Alastair Stewart that he was “calling” the election for John Kerry. We went to bed elated and rose to deflation. Worcester was subsequently knighted for services to misinformation.

There is a more reliable guide to political sympathy than opinion polls. It is actual votes in ballot boxes. Five mainland by-elections were held last year, the last just a week before ICM completed its fieldwork for the findings published on December 26th. Even taking into account the distortion caused by the vote at Inverclyde in June (where the SNP advanced against all other parties but Labour held on), the average increase in Labour’s vote in the five polls was 8.9 per cent. In the first three of these by-elections, each called in circumstances that normally would lead to a certain resentment of the defending party, Labour increased its vote by an average of 11.9 per cent. At Feltham and Heston on December 15th, it was 8.6 per cent and here, for the first time in any of these ballots, the Tories came as high as second. Difficult to found an image of “Cameron in command” on these results.

But the Tory press – and, under its influence, the supposedly disinterested broadcast news – prefers the reading of the polling organisations because it suits their agenda. The Guardian too is happier with the ICM data than with real votes: after all, it still has to justify its journalism that relentlessly undermined Gordon Brown and its editorial support of the Liberal Democrats at the general election that helped to bring about the coalition with the Tories.

Labour’s new Executive Director of Rebuttal should quickly establish the convention that Labour discounts opinion polls and only recognises voting results. Every time Martha Kearney or Jeremy Paxman tells a Labour representative that the party is doing badly in the polls, the response should be to quote the by-elections. And when and if a by-election proves bad for Labour, it can be addressed as a real rather than a fantasy problem. There is much rebuilding to be done.

Tags: Domestic (UK)Categorised in: Article

This post was written by W Stephen Gilbert