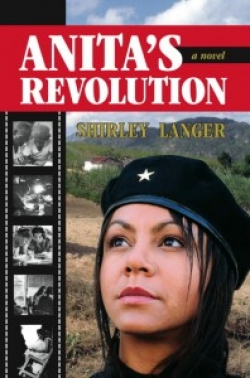

A review of Anita’s revolution

April 19, 2013 12:00 am Leave your thoughts In these days of economic and cultural uncertainty and social media dominance, the book industry is dominated by caution. Is it sexy? Will it sell? Is the author’s face advertising- friendly? Such questions are an all-too-common editorial litany.

In these days of economic and cultural uncertainty and social media dominance, the book industry is dominated by caution. Is it sexy? Will it sell? Is the author’s face advertising- friendly? Such questions are an all-too-common editorial litany.

Some books are too important to ignore and they require special dedication (the wings of angels) if they are going to find their moment. In the case of Anita’s Revolution, a narrative which should resonate with many young men and women approaching their wandering years, Shirley Langer is her own angel. This is the new reality for authors of good books that don’t make the cut in a culture dominated by super pacs and super-sizing.

Langer lived and worked in Cuba for five years in the Sixties, just after the revolution that freed the island nation from colonialism and despotism, the exploitation of the Pearl of the Antilles by the Spanish and American governments and organized crime. We don’t need to remind ourselves that freedom is fragile. The new regime began with the nationalization of property and elimination of racial discrimination The first step in strengthening the oppressed campesinos of Cuba, many of them descendents of slaves brought to harvest the sugar cane, was literacy. Literacy is power, the power to learn and the opportunity to make critical life choices. This was and is a top priority in Cuba, whose children enjoy one of the finest educational systems in the world: no child left behind.

In 1961, two years after the revolution, the new government declared their intention to create a territorio libre de analfabetismo and organized an army of volunteers to eliminate illiteracy. In an unprecedented rite of passage, thousands of teens and pre-teens, called brigadistas, left the comfort of their homes and schools to reverse the plague of illiteracy, while nearly one million Cubans of all ages, the eldest 106, waited for the power of language to lift them out of poverty and despair.

Adolescence is a time of extremes. As they lurch into the gap years between dependence and independence, young adults identify with their peers and with ideals their parents have compromised. Fidel and his compadres chose an ideal teacher group, as this army of friends got their first taste of personal freedom and developed their self-worth.

Anita is a part of the privileged upper middle class of Old Havana. Her father is a liberal newspaper editor, an enlightened friend of the revolution in the days before total US embargo. His family was still enjoying a standard of living completely foreign to many Cubans. Idealism is Anita’s birthright and the prevailing social environment. She and her brother are determined to become brigadistas, volunteers in the army of literacy teachers in spite of the counter-revolution and their parents’ understandable fear for their safety. Like many of her peers, Anita chooses to rebel and help at the same time, strengthening not only herself but also the future of Cuba.

Langer knew Cuba intimately during this unique time when the forces of change and resistance led to uncivil war when even the army of youth volunteers were persecuted by those who feared social change. She has written Anita’s narrative with the authenticity it requires. She knows the back-story, has absorbed the empirical setting and interviewed the real characters in her documentary novel. This book feels like Cuba, its intonation and tensions, its exhausted but resolute idealism.

Others have written about Cuba, a country which captures the heart and the imagination with its lush diversities of culture and potential and its heartbreaking persecution by colonial powers, but this is a special book because it is written for an audience that needs to hear that it has permission to heal a broken world.

Anita, who is candid about her weaknesses, is strength. She opposes her parents to do what is right even when it seems wrong. Her journey is dangerous but ultimately rewarding as she engages the true meaning of family.

Would that all adolescents had similar opportunities in their wandering time. A recent study shows that children who question parental authority have more strength of character in making appropriate personal decisions. Anita’s story supports the notion that the greatest privilege we can afford young men and women is the opportunity to risk doing good and learning their own potential. Anita lost nothing by taking a year out of her studies and she gained the world. Now, half a century later, she and the hundreds of thousands can look back and say they made the revolution a reality that changed the lives of millions.

UNESCO has designated Cuba, a country with a poet as one of its great national heroes, almost 100% literate.

I recently told an audience of young Cubans at the University of Havana that, contrary to what they might hear in the American media, they were the advantaged youth generation because they already knew how to deal with adversity, how to live with less and without contamination of their environment. This is the legacy of the brigadistas.

Within and without Cuba, there is dissent about the great social experiment. No system is perfect, especially one that labours under the boot of American imperialism directed by wealthy Cuban expatriates, the former ruling class. There is no argument though about an educational system which produces exemplary standards.

This is a basic human right, one that the children of Cuba earned and one that they continue to cherish. It is the backbone of this slender island. Anita’s story is the story of Cuba libre and a cautionary tale for all who mistake dissent for disrespect. Even though its target audience is young people, perhaps some adults – that would be all parents and teachers – should read Anita’s Revolution as well.

Linda Rogers is a friend of Cuba and author of the novel Friday Water, based on her understanding of the amazing culture and fortitude of the Cuban people.

Tags: Latin AmericaCategorised in: Article

This post was written by Linda Rogers