Everything is information, you have to choose. An interview with Jean-Philippe Tremblay

July 22, 2013 12:00 am Leave your thoughts

Jean-Philippe Tremblay is a Canadian film director based in London whose latest work, Shadows of Liberty http://shadowsofliberty.org/, is an inspiring and rich documentary about freedom of information. He spent over 5 years researching and interviewing people who believe in freedom of information and have been fighting the establishment and going against governments and corporations to let the truth emerge.

Inspired by “The New Media Monopoly”, a book written in 1984 by Ben Bagdikian, Shadows of Liberty is a quest for truth, showing how the media has been manipulated and information distorted to create a manufactured consent based on profits to justify corporations and governments. Yet, in the past decades, many activists, journalists and academics have spoken out and paid for their choice and their belief in freedom of information: Shadows of Liberty includes interviews with many key players including Amy Goodman, Julian Assange, David Simon, Jeff Cohen, Robert McChesney, Chris Hedges, John R. MacArthur, Dick Gregory, Daniel Ellsberg, Kristina Borjesson, Bob Baer, Norman Solomon, John Nichols and Roberta Baskin, to name a few, who Jean-Philippe Tremblay interviewed to let their stories emerge and provide a deeper insight into the media control our society is subject to. When I invited Jean-Philippe for a Lego-based interview, he immediately accepted: he liked the idea of a different way of conducting an interview. He has a curious and inquisitive mind, open to experimenting. When we sat at the table and Jean-Philippe saw the Lego bricks, he smiled and said:

“I am very happy because when I was a kid I always had Lego [bricks] ‘ I have’t played since that time”. I explained the interview process: “This is not about building, this is just a medium to let new ideas emerge”

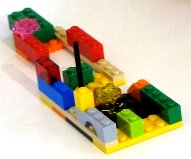

“What is information?” I ask. He takes his time, looks at the bricks, and starts thinking. Once he has finished and is happy with his model, he starts to discuss the model he has built.

“I guess that information is blocks of information. I guess you have different types of information and that’s why I’ve used different colours and different shapes, because information can represent anything: you can have information about so many different things, it’s about everything actually.”

“What are those blocks made of?” I ask

He replies “You get information by everything. You get information from this table, you get information from a newspaper, from a book, you get information from films and all source of things’ As long as your eyes and your ears and all your senses are actually affected by something, that gives you information. So information is everything.”

“How are those blocks connected?” I reply

Tremblay answers: “Actually there’s nothing really that connects them, except just the physical connection. And it’s quite disorganised in a way, at the same time, [it’s] organised physically, but disorganised in terms of shape and colour.”

“And how do you organise it?”

“You have to manipulate it, you have to observe it, you have to understand it. The way I would approach it would be to learn about it, observe it to see what information looks like, to see where it is in its environment and you can think about it actually and ask questions about it.”

“What are those light transparent bricks over there?” I ask whilst pointing at a few transparent bricks in his model.

“That’s just to represent a different kind of information, I think. I was looking at the colours and I thought [about] using almost every single piece that was different just to make the point that it’s so different. This antenna could represent the same thing of the building.”

[In the first part of the interview, while talking about filmmaking, Jean-Philippe focused on the antenna as a way to make the film seen and as a key element of filmmaking – the first part is available at http://legoviews.com/2013/06/28/jean-philippe-tremblay-filmmaking-is-about-the-team/]

He continues “It could be about broadcast waves and radio waves, so it could be communication”

“Information is given or taken? What is this antenna doing?”

“I think it’s a bit of both” Tremblay replies “I think information surrounds us all the time, and this is why to me this kind of represents everything. It’s up to one to do want they want with it. You can actually take it or give it, I think you can do both and it’s important to do both. On one hand, if you take it, you let the information sink in. If you give it, I guess maybe you are giving an opinion. I think this is maybe a good way to describe taking or giving information.”

“How do you select what you take and what you give away?” I enquire

“As we were talking about the base of filmmaking, you really have to decide what the vision for that is and how you want to represent that information. So it’s a choice and that choice is made by the kind of person you are, or by the kind of work you do, or what kind of work you want to do. So it’s always a choice.”

I respond by saying “Information is not continuous in your model, there are holes, ups and downs, steps”

“What is fantastic in the world is that [it] is full of holes and full of gaps, but you also have some strong pieces. Because if everything is information that means there are so many possibilities and so much information out there.”

“Is it good to have so much information?”

“I think in a way it depends on how you look at it. Because I think information is everywhere. I mean it comes back to the question of what information is and I think it’s about your senses being sensitised or activated or affected and that happens all the time. We don’t have a choice as human beings, we are always feeling something, communicating with the world around us”

“But there is no human being here” I notice looking at his model.

“If you want, my humanity is represented by this eye”, he says while showing me the eye-shaped brick. “It’s less of a human being and more the sense. It’s more a vision.”

I invite Tremblay to play with his model and see what happens if a human figure is added. He accepts the challenge and adds a human figure to his model and he becomes surprised by the result.

“It looks mean!” he says. “He (the figure) looks very active, he looks [like] he is about to jump in this thing. It’s quite interesting, because it is kind of representing what the senses feel when you actually feel something, or when you touch something, or hear something or see something, whether it is a tree or a table or a book that you are reading or a film that you are experiencing. I like the way that this person is reacting. You know, there’s a sense of excitement, [as if] this person is going to interact with information. I guess before filmmaking, this what you have: you have information. So it’s gathered, it’s not organised. In filmmaking, whether you like it or not, you have to organise something, you have to make the choice you have to pick up your camera and shoot something or talk to someone or follow something. So I think that before the process of filmmaking this is what information looks like, it is not organised but it’s beautiful in its own way”

“If everything is information, what is not information?” I probe. “What about those gaps?” I ask showing him the holes and gaps in his model.

“I think it’s important to have gaps, holes and different things like that. Because the hole is something: when there is nothing there, that is information – nothingness is information too. So although I think it is quite useful to have this physical information, it is also quite nice to have blank information as well. I think that could be quite useful when working with all this information at the same time”

“In your film you are against a certain kind of information. Is that kind of information, still information? Is hidden information, or biased information, still information?” I ask him.

“Yes absolutely. I don’t think I am against information: in a way we don’t have the choice to live without information because we always feel something, our senses are always sensitised, we are always active, our mind is always thinking something. I guess what I represent in the film [is] that this is one gathering of information that dominates everything else and I guess that’s how I explain in the film: we have one very powerful view that dominates every other view. That could be dangerous for society and what we need is many views, views not motivated by money or power. What the film says is that we want to know the truth about a certain story”

I can not resist asking the next question: “Is information the truth?”

“It’s a way of trying to get to a certain truth. It is a good question: is there a real truth? You can say truth is that I have been driven here to this interview, so that’s a truth, it’s hard to argue with that”

“It’s a fact” I point out to challenge him.

“It’s a fact” he echoes.

“So, are facts true?” I insist.

“Yes, but I think it also depends on who tells any kind of fact. You know, the same fact can have two different stories or many different stories, and that’s why I think it’s important to have many different views because that’s how you can try to get to the truth. You don’t just talk to one person, you have to talk to many different people from different backgrounds, people who have a different perspective to that fact. So I think it’s really about communication”.

“Is there any truth in this model?”

“Well, what it’s truth?” he says. “The truth is that this block here is red”, he says showing me a red brick. “We can say that it is true that this is red but that’s on a very simple kind of level. You can get into it more specifically and more philosophically about what is red. Many different people in the world may describe this as ‘not red’ because this is red as well” he says pointing at another transparent red brick. “But it’s a different kind of red” he adds. “So I think it’s important to really be aware and to actually take time: if you want to learn about information, and possibly truth, you need time to communicate with a lot of different people with different perspectives. Then you might get close to the truth and get some interesting responses too”.

We end our interview with the concept that there is no one absolute truth and the only way to get close to a truth is to communicate with as many different people as possible in order to get a wider picture. After all, what Jean-Philippe Tremblay said during the interview is no different from what he has done in his documentary: he showed how much information is hidden by vested interests and he has taken time to talk to many different people who are trying to outline and represent the truth about the media. That truth that you won’t find in the media itself.

Categorised in: Article

This post was written by Patrizia Bertini