Hannibal ad Portas

September 14, 2014 12:00 am Leave your thoughts

The last war has come to an end, the next war has not yet started, so let’s use the time to speak of many things. Of Hannibal, for example.

Hannibal? The man with the elephants?

The very same.

Hannibal, the Carthaginian commander who is considered one of the military geniuses of all times, was a hero of my youth.

At the time, we were in dire need of national heroes. Anti-Semites all over the Western world were claiming that the Jews were cowards by nature, shirkers unable and unwilling to fight like men. They just collected the money while others died for them.

Looking for heroes, we found Hannibal. Carthage was founded by refugees from Tyre in South Lebanon, whose inhabitants were Canaanites who spoke a dialect very close to Hebrew. The name of Carthage is derived from the Hebrew Keret Hadasha (New City”), and the name Hani-Ba’al means Ba’al, the Canaanite God, has given – more or less the same name as Netanyahu – Yahu, short for Jehovah, has given. Like Theodor as in Herzl and Dorothy as in de Rothschild.

Who could be closer to our heart then this great fighter, who led his army, with its dozens of elephants, across the Alps into North Italy, who gave his orders in Hebrew? Even the mighty Romans paled when they heard the shout: “Hannibal ad portas” (“Hannibal near the gates”, often falsely quoted as “ante Portas”)!”

One of the greatest Zionist poets, Shaul Tchernichovsky, the translator of Homer’s Odyssey, affirmed our closeness to the Carthaginians, telling us that they were the greatest maritime force in the ancient Mediterranean, even before the Greeks. We were proud of them.

In a strange way, Hannibal came up in the recent Gaza war. Not that any of our commanders were modern-day geniuses. Far from it. But something called the “Hannibal procedure” was one of its most terrible phenomena.

Who coined the term? Some officer with an inclination for ancient history? Or just an insensitive computer, the same which called this war “Solid Cliff” – while a human robot gave it the English name “Protective Edge”?

At the height of the fighting near the town of Rafah (Rafiah in Hebrew) on the Egyptian border, a squad of Israeli soldiers were trapped by Hamas soldiers and most of them were killed. One Israeli was dragged by the Palestinians into a tunnel. The first impression was that he was captured alive, perhaps wounded.

The Hannibal Procedure went into action.

The Hannibal Procedure is designed for just such an eventuality. Of all the nightmares (or rather daymares) of the Israeli army, this is one of the worst.

This needs some explaining. In war, soldiers fall into captivity. Often this is unavoidable. In combat situations, in which further resistance becomes senseless suicide, soldiers raise their hands.

In medieval times, prisoners-of-war were often held for ransom. For officers and political leaders that was a welcome source of income, a good reason for keeping prisoners alive and well. In more modern times, after the laws of war came into being, prisoners are exchanged when the war ends.

During World War II, many Jewish soldiers from Palestine who had volunteered for the British army fell into German captivity. Surprisingly, they were treated like all other British prisoners-of-war and returned safely home when it was over.

There is nothing dishonorable about being captured. True, Stalin sent multitudes of returning Soviet prisoners to penal camps in Siberia, not because they were dishonored but because he was afraid that they had been infected by capitalist ideas.

So why are we different?

Jewish ethos is quite explicit about this. The “redemption of prisoners” is a paramount commandment of the Jewish religion.

At the root of this moral order is the ancient phrase “(the people of) Israel are responsible for each other”. Every Jew is responsible for the survival of every other Jew.

This had to be taken literally. If a Jew from Alexandria was taken prisoner by Turkish pirates, rich Jewish merchants in, say, Amsterdam were obliged to pay the ransom to get him released. This is very deeply ingrained in Jewish consciousness, even in contemporary Israel.

During the wars of 1948, 1956, 1967 and 1973, when the Israeli army was fighting Arab regular armies trained by Europeans, prisoners were taken by both sides, generally reasonably well treated and exchanged after each war. But when the Israeli-Palestinian conflict became “asymmetrical”, things became more complicated. On the one side a regular army, on the other hand armed militants (a.k.a. freedom fighters, a.k.a. terrorists).

Israel holds a large number of Palestinian prisoners, some sentenced, some held in “administrative detention” (i.e. on suspicion only). Their number varies between 5000 and 12,000. Some are political prisoners, some active members of fighting organizations (“terrorists”). Some have “blood on their hands”, meaning that they either did the killing themselves or helped the killers by hiding them or providing them with money or weapons.

For many Palestinians, it is a holy duty to get them released. For many Israelis, this is a crime. The result: constant efforts by Palestinians to capture live Israelis, in order to exchange them for these prisoners.

The tariff is going up all the time. When Palestinians demand a thousand of their prisoners in return for one Israeli, Israelis are outraged, but also flattered. Many indeed believe that this tariff is fair, but they are outraged nevertheless. In 1985, three Israeli soldiers held by a pro-Syrian Palestinian organization were exchanged for 1150 Palestinian prisoners.

In every such event, Israelis are torn between the obligation to “redeem prisoners” and the determination “not to deal with terrorists” as well as “not to surrender to blackmail”, especially concerning prisoners with “blood on their hands”.

The first priority is always to try to release Israeli prisoners by force. This is a very risky undertaking. In the ensuing shooting, the prisoner’s life is at risk. Often it is uncertain whether he was killed by the captors or by the liberators.

The Israeli sportsmen who were killed during the Munich Olympic games of 1972 were probably killed by the poorly trained Bavarian police. The autopsy results are still secret. The same happened to a class of Israeli schoolchildren in Ma’alot in Northern Galilee, who were captured by Palestinian guerrillas and perished in the exchange of fire.

In the famous Entebbe operation, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was ready for a prisoner exchange until he was persuaded by the army that the rescue operation had a very good chance of success.

The dilemma reached its peak in the Gilad Shalit affair. The soldier was captured (“kidnapped” in Israeli parlance) by Palestinians who emerged from a cross-border tunnel. (Our army drew no tactical conclusions from the incident, until the latest war).

Shalit was held in captivity for five years. Frantic efforts by the army to discover his place of captivity bore no fruit (luckily for Gilad, I must add). From week to week the public pressure for an exchange grew, until it became politically unbearable and Shalit was exchanged for 1027 Palestinian prisoners. The army was furious, and on the first opportunity rearrested all those who had been released.

The latest round of negotiations directed by John Kerry broke down because Netanyahu refused to free a number of prisoners he had already undertaken to release.

Somewhere on the way, the Hannibal Procedure was instituted.

This order is based on the conviction that prisoner exchanges must be prevented by all means – quite literally.

In such cases, the first few minutes are decisive. Therefore, “Hannibal” puts the entire responsibility on the local commander, even if he is a mere Lieutenant. No time for waiting for orders.

When soldiers see their comrade being dragged away, they must shoot and kill – even if it is almost certain that their comrade will also be hit. The order does not say explicitly “better a dead soldier than a captured soldier” – but this is implied and widely understood that way.

If the captors and their captive disappear, the whole neighborhood has to be flattened indiscriminately, in the hope that the captors are hiding in one of the buildings.

At the height of the Gaza war, that is exactly what happened. An Israeli squad fell into a Hamas ambush. All the soldiers were killed, except one – Hadar Goldin – who was seen being dragged into a tunnel. Assuming that he was captured, the army went berserk, razing scores of buildings in Rafah to the ground without warning, shooting at everything that moved.

In the end, it was all in vain. The army decided that the soldier was already dead when his body was captured, and now demands the return of the body, so as to fulfill another Jewish duty: “to bring a Jewish body to a Jewish grave”.

During and after the war, this incident led to a furious debate. Why, for God’s sake, not let soldiers be captured? Isn’t a live captured soldier better than a dead one? If for his return a number of Palestinian prisoners have to be released, so what?

This is a profound moral debate, touching the roots of the Israeli ethos.

David Ben-Gurion once wrote: “Let every Hebrew mother know” that she is handing over her son to responsible officers. Thanks to Hannibal, some Hebrew mothers may now have serious doubts.

As for Hannibal himself, I wonder what he would have thought about this.

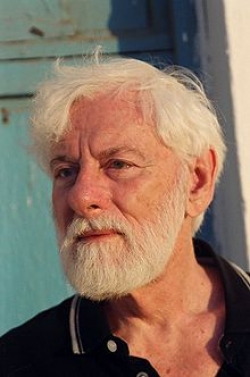

Uri Avnery is an Israeli journalist, co-founder of Gush Shalom, and a former member of the Knesset

This article first appeared on the website of Gush Shalom (Peace Bloc)- an Israeli based peace organization

http://zope.gush-shalom.org/home/en/channels/avnery/1410551425/

Tags: Middle-EastCategorised in: Article

This post was written by Uri Avnery