Imagined Nations

December 27, 2015 10:48 pm Leave your thoughts

Two weeks ago, Benedict Anderson died. Or, as we say in Hebrew, “went to his world”.

Anderson, an Irishman born in China, educated in England, fluent in several South Asian languages, had a large influence on my intellectual world.

I owe a lot to his most important book, “Imagined Communities”.

Each of us has a few books that formed and changed his or her world view.

In my early youth I read Oswald Spengler’s monumental “Der Untergang des Abendlandes” (The Decline of the West). It had a lasting effect on me.

Spengler, now nearly forgotten, believed that all the world’s history consists of a number of “cultures”, which resemble human beings: they are born, mature, grow old and die, within a time span of a thousand years.

The “ancient” culture of Greece and Rome lasted from 500 BC to 500 CE, and was succeeded by the ‘magic” Eastern culture that culminated in Islam, which lasted until the emergence of the West, which is about to die, to be succeeded by Russia. (If he had lived today, Spengler would probably have substituted China for Russia.)

Spengler, who was a kind of universal genius, also recognized several cultures in other continents.

The next monumental work that influenced my world view was Arnold Toynbee’s “A Study of History”. Like Spengler, he believed that history consists of “civilizations” that mature and age, but he added a few more of them to Spengler’s list.

Spengler, being German, was glum and pessimistic. Toynbee, being British, was up-beat and optimistic. He did not accept the view that civilizations are doomed to die after a given life-span. According to him, this has indeed always happened until now, but people can learn from mistakes and change their course.

Anderson dealt only with a part of the story: the birth of nations.

For him, a nation is a human creation of the last few centuries. He denied the accepted view that nations have always existed and only adapted themselves to different times, as we learned in school. He insisted that nations were “invented” only some 350 years ago.

According to the Europe-centered view, the “nation” assumed its present form in the French revolution or immediately prior to it. Until then, humanity was living in different forms of organization.

Primitive humanity lived in tribes, generally consisting of about 800 human beings. Such a tribe was small enough to live off a small territory and big enough to defend it against neighboring tribes, which were always trying to take the territory away from it.

From there, different forms of human collectives emerged, such as the Greek city states, the Persian and Roman empires, the multi-communal Byzantine state, the Islamic “umma”, the European multi-people monarchies, and the Western colonial empires.

Each of these creations suited its time and realities. The modern nation state was a response to modern challenges (“challenge and response” was Toynbee’s machine of change). New realities – the industrial revolution, the invention of the railway and the steamship, ever deadlier modern weapons etc – made small principalities obsolete.

A new design was necessary, and found its optimum form in a state consisting of tens of millions of people, enough to sustain a modern industrial economy, to defend its territory with mass armies, to develop a common language as a basis of communication between all citizens.

(I ask for forgiveness if I am mixing my own primitive thoughts with those of Anderson’s. I am too lazy to sort them out.)

Even before the flowering of the new nations, England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland were forcibly united in Great Britain, a nation big and strong enough to conquer a large part of the world. French, Bretons, Provencals, Corsicans and many others united and became France, taking immense pride in their common language, fostered by the printing press and mass media.

Germany, a latecomer on the scene, consisted of dozens of sovereign kingdoms and principalities. Prussians and Bavarians loathed each other, cities like Hamburg were proudly independent. Only during the French-Prussian war of 1870 was the new German Reich founded – practically on the battlefield. The unification of “Italy” took place even later.

Each of these new entities needed a joint consciousness and a common language, and that is where “nationalism” came in. “Deutschland Ãœber Alles”, written before the unification, did not mean originally that Germany was set above all nations, but that the common German fatherland stood above all the local principalities.

All these new “nations” were out to conquer – but first of all they “conquered” and annexed their own past. Philosophers, historians, teachers and politicians all set out eagerly to re-write their past, turning everything into “national” history.

For example, the battle of the Teutoburg forest ( 9 CE), in which three German tribes decisively defeated a Roman army, became a national “German” event. The leader, Hermann (Arminius), posthumously became an early “national” hero.

This is how Anderson’s “imagined” communities came into being.

But according to Anderson, the modern nation was not born in Europe at all, but in the Western Hemisphere. When the immigrant white communities in South and North America were fed up with their oppressive European masters, they developed a local (white) patriotism and became new “nations” – Argentina, Brazil, the United States and all the others – each a nation with a national history of its own. From there the idea invaded Europe, until all humanity was divided into nations.

When Anderson died, nations were already starting to break up like antarctic icebergs. The nation state is becoming obsolete, and rapidly becoming a fiction. A world-wide economy, supernational military alliances, space flight, world-spanning communications, climate change and many other factors are shaping a new reality. Organizations like the European Union and NATO are taking over the functions once performed by nation states.

Not by coincidence, the unification of geographical and ideological blocs is accompanied by what seems the opposite tendency, but is in reality a complementary process. Nation states are breaking apart. Scots, Basques, Catalans, Quebecois, Kurds and many others clamor for independence, after the breakup of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Serbia, Sudan and several other supranational entities. Why must Catalonia and the Basque country live under the same Spanish roof, if each of them can become a separate, independent member of the European Union?

A hundred years after the French Revolution Theodor Herzl and his colleagues “invented” the Jewish nation.

The timing was not accidental. All of Europe was becoming “national”.

The Jews were an international ethnic-religious Diaspora, a remnant of the ethnic-religious world of the Byzantine Empire. As such, they aroused suspicion and enmity. Herzl, an ardent admirer of both the new German Reich and the British Empire, believed that by redefining the Jews as a territorial Nation, he could put an end to anti-Semitism.

Belatedly, he and his disciples did what all the other nations had done before: inventing a “national” history, based on Biblical myths, legends and reality, and called it Zionism. Its slogan was “If you will it, it is no fairy tale”.

Zionism, helped by intense anti-Semitism, was incredibly successful. Jews established themselves in Palestine, created a state of their own, and in the course of events became a real nation. “A nation like all the others”, as a famous slogan said.

The trouble was that in the process, Zionist nationalism never really overcame the old Jewish religious identity. Uneasy compromises struck for expediency’s sake blew up from time to time. Since the new state wanted to take advantage of the power and financial means of World Jewry, it was quite happy not to cut the ties and pretend that the new nation in Palestine (“Eretz Israel”) was only one of many Jewish communities, although the dominant one.

Unlike the process of cutting themselves off from the motherland, as described by Anderson, the feeble attempts to constitute in Palestine a new separate “Hebrew” nation, like Argentina and Canada, failed. (They are described in the books of Shlomo Sand.)

Under the present Israeli government, Israel is becoming less and less Israeli, and more and more Jewish. Kippah-wearing religious Jews are taking over more and more of the central government functions, education is becoming more and more religious.

Now the government wants to enact a law calling for the “Nation State of the Jewish People”, overriding the existing legal fiction of a “Jewish and democratic State”. The fight about this law may well be the decisive battle for Israel’s identity.

The concept itself is, of course, ridiculous. A people and a nation are two different concepts. A nation state is a territorial entity belonging to its citizens. It cannot belong to the members of a world-wide community, who belong to different nations, serve in different armies, shed their blood for different causes.

It also means that the state does not belong to 20% or more of its own citizens, who are not Jews at all. Can one imagine a constitutional change in the US, declaring that all Anglo-Saxons world-wide are US citizens, while African-Americans and Hispanics are not?

Well, perhaps Donald Trump can. Perhaps not.

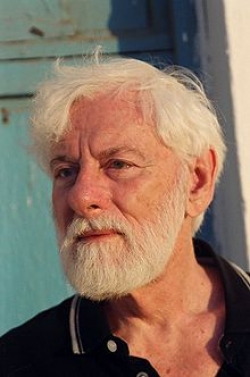

Uri Avnery is an Israeli journalist, co-founder of Gush Shalom, and a former member of the Knesset

This article first appeared on the website of Gush Shalom (Peace Bloc)- an Israeli based peace organisation

http://zope.gush-shalom.org/home/en/channels/avnery/1451055858/

Tags: Middle-EastCategorised in: Article

This post was written by Uri Avnery