The Call of the Mu’ezzin

November 25, 2016 12:00 am Leave your thoughts

The first mu`ezzin stood on the roof of the prophet Muhammad’s home in Medina, during his exile from Mecca, and called the believers to prayer. He also walked along the streets, doing the same.

When Islam became the established religion, minarets were built. Their original purpose was to ventilate the mosque, letting the hot air out and thus drawing the cooler air in. The mu’ezzin climbed to the top and intoned the ‘azzan, the call to prayer. Often a blind man was chosen, so he could not look into the homes below.

The word is closely connected with the biblical and modern Hebrew word “ha’azinu” (“listen”).

Lately, electric loudspeakers make the job of the mu’ezzin much easier. Nowadays, he can sit below and use a microphone. If a recording is used, the mu’ezzin becomes altogether superfluous.

Anyway, the voice of the mu’ezzin must come forth five times a day and call the believers to prayer, which is one of the five pillars of Islam.

The first call is sent out before dawn. And there’s the rub, as Hamlet would have said, if there had been minarets in Denmark in his time.

Since Palestine was conquered by the army of the Khalif Omar in the year 636 A.D., the voice of the Mu’ezzin has been heard five times a day in most of the country’s towns and villages. (Some Arab villages remained Christian and sounded bells).

No more, if Yai’r Netanyahu has his way.

Yair (25) is the crown prince in Israel’s royal family. He is the darling of his assertive mother and walks around with four bodyguards paid for by the taxpayer (me). He seems to be a nice if nondescript person. He loves nightclubs and luxury. He also likes his sleep.

But how can one sleep in Jerusalem if a nearby mu’ezzin wakes one up at 4 o’clock in the morning?

This is not only Ya’ir’s problem. Many Jews in Israel live near mosques, especially in mixed towns like Jerusalem, Haifa and Jaffa. The mu’ezzin wakes them up in the middle of their sweetest dreams, just when the beautiful maiden is about to give in (or vice versa for women). They may be furious, but they know that they can do nothing about it.

But Ya’ir can.

He has induced his father to propose a bill that would forbid the use of loudspeakers in all houses of worship. When the powerful Jewish orthodox faction protested, since this would also forbid the call to Shabbat, the bill was amended and now mentions mosques specifically. This may be annulled by the Supreme Court on grounds of discrimination. In the meantime, Ya’ir is still aroused from his precious sleep.

(Actually, there is already a law in Israel that forbids making noise before 7 a.m., but it is not applied).

All this sounds funny. But it isn’t. It may be a farce, but it symbolizes one of Israel’s most serious problems.

Only 75% of Israelis are Jews. 21% are Arabs, mostly Muslims, some Christian. The rest are Jewish non-Jews – for example, people whose father was Jewish but whose mother was not.

What is the status of this large Arab minority in a state that defines itself officially and legally as “Jewish and democratic”?

The Arabs are Israeli citizens, with all the rights conferred by citizenship. But are they really Israelis? Can Arabs really be full-fledged citizens in a “Jewish” state?

Worse, Israel is a small though powerful island in the Muslim sea. Israel has an official peace agreement with two Arab states – Egypt and Jordan – but it has never really been accepted by the Arab masses anywhere. Several Arab states have been legally in a state of war with Israel since 1948.

Even worse, Israel rules and oppresses an entire Arab people, the Palestinians, a people deprived of all rights, national as well as human. The Arabs within Israel consider themselves a part of this Palestinian people. Lately they prefer to call themselves “Palestinian citizens of Israel”.

Many countries have a national minority, and each grapples with this problem in its own way. But the situation of the Arab – sorry Palestinian – minority in Israel is unique.

During the first years of Israel, it was hoped that the “Israeli Arabs” (a term they detest) would serve as a bridge between Israel and the Arab world. An Arab friend of mine politely declined, saying that “a bridge is something people trample upon.”

As long as David Ben-Gurion was in power, Arab citizens were subject to a “military government”, without whose permission they could not leave their town or village, nor do much else. This was used to blackmail them into snitching on their fellow-Arabs.

After a long battle by many of us, this regime was abolished in 1966. But the basic problem of the Arab minority was not solved.

In a country with a large national minority, the majority people is faced with a choice: either confer on all citizens equal rights in every respect, or confer on the minority a special national status with some measure of autonomy.

Israel did what it always does when faced with such a choice: it does not choose. The question remains open.

Can there really be equal rights for non-Jews in a state that defines itself as “Jewish and democratic”? Of course not. The most important law, the “Law of Return”, confers on every single Jew in the world the automatic right to immigrate to Israel. Contrary to the impression given, this right does not stand alone: it is connected with several other laws. A Jewish immigrant automatically becomes a citizen (unless they expressly decline). Several material rights, not generally known, are also connected with this.

Arabs, of course, do not have any of these rights. The huge quantity of mobile and immobile property left behind by the 750,000 Arab refugees who fled or were expelled during the 1948 war and later, was expropriated without any compensation.

If there is no real equality, what about the other alternative: granting them the official status of a national minority, with some form of autonomy?

It is ironic that the official forefather of the Likud, Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky, a brilliant right-wing Zionist, was in his youth the author of the “Helsingfors plan”, a detailed proposal for the status for all minorities in Czarist Russia. This plan, which also formed the basis of Jabotinsky’s doctoral thesis, proposed autonomy for every national minority, even if (like the Jews) they had no territory.

This could be an excellent plan for the Palestinian minority in Israel, but the Likud, of course, would not dream of accepting it. Like the anti-Semites in Czarist Russia, today’s right-wing Israelis consider the national minority a potential or actual fifth column, and any form of autonomy for them a danger to the state.

Lovers of the Bible may find some amusement in the words of Pharaoh (Exodus 1) about the Children of Israel: “When there falleth out any war, they join also unto our enemies and fight against us.” By a curious turn, now we are Pharaoh, and the Arabs are the new Children of Israel.

So what is the situation of Israel’s Arab citizens?

It is neither a situation of real equality, as Israeli propagandists assert, not is it a terrible situation of suffering and oppression, as painted by irrational haters of Israel. The actual situation is far more complex.

This week I was in a supermarket in Tel Aviv. I collected some articles and went to pay. I was served by a very good-looking young cashier, who spoke perfect Hebrew and was also extremely polite. When I left, I was a bit surprised to realize that she was Arab.

Some time ago I was hospitalized (forgot for what) in Tel Aviv. The chief doctor of the department was an Arab. Also many of the male nurses. Contrary to the image of the wild, savage Arab, it is generally agreed that Arab nurses, male and female, are much gentler than their Jewish counterparts.

A respected Supreme Court judge, who also sits on the committee for appointing judges, is an Arab.

Arabs are deeply embedded in the Israeli economy. Their average income may be lower than the Jewish one, especially since much fewer Arab women than Jewish ones work. But Israeli living standards are much higher than in any Arab country.

I think that Arab citizens are much more “Israelized” than most of them realize. It is only when they visit Jordan, for example, that they feel they are different (and superior).

While they do not enjoy autonomy, in practice there is a “supervising committee” that unites all Arab municipalities and associations, and there is the Joint Arab faction (the third largest faction in the Knesset)

That is one side of the ledger. The other side is the very opposite: Arab citizens feel every day that they are different from the Jews, that they are looked down upon and discriminated against. Not even the Jewish Left dreams about setting up a government coalition with the Arab faction.

There is a hidden debate inside Arab society in Israel. Many Arabs believe that their faction in the Knesset should deal more with their situation in Israel, while the faction itself deals much more with the situation of their brothers and sisters in the occupied Palestinian territories.

There used to be a well-known Yiddish saying: “It isn’t easy to be a Jew”. In the Jewish State, “it is not easy to be an Arab”.

All these dilemmas are somehow symbolized by the proposed law of the Muslim prayer call.

Of course, the problem could be solved by mutual discussion and understanding. In all Arab towns and villages, people want to hear the call to prayer, even if many of them do not get up to go to the mosque. In neighborhoods with a non-Muslim population, the loudspeakers could be silenced by agreement, or their volume lowered. But prior to submitting the bill, there were no consultations at all.

So if Yai’r is woken up at 4 o’clock in the morning, perhaps he could devote the next hour to thinking about how to reach an understanding between the Jews and their Arab neighbors.

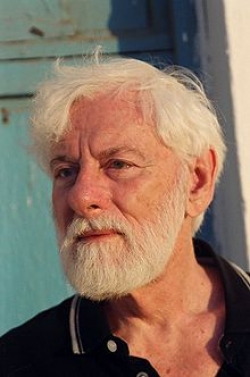

Uri Avnery is an Israeli journalist, co-founder of Gush Shalom, and a former member of the Knesset

This article first appeared on the website of Gush Shalom (Peace Bloc) – an Israeli peace organisation

http://zope.gush-shalom.org/home/en/channels/avnery/1480100372/

Tags: Middle-EastCategorised in: Article

This post was written by Uri Avnery