Parliamentary Riffraff

May 20, 2017 5:17 pm Leave your thoughts When I first entered the Knesset, I was shocked by the low standard of its debates. Speeches were full of clichés, platitudes and party slogans, the intellectual content was almost nil.

When I first entered the Knesset, I was shocked by the low standard of its debates. Speeches were full of clichés, platitudes and party slogans, the intellectual content was almost nil.

That was 52 years ago. Among the members were David Ben-Gurion, Menachem Begin, Levi Eshkol and several others of their kind.

Today, looking back, that Knesset looks like an Olympus, compared to the present composition of that non-august body.

An intelligent debate in today’s Knesset would be as out of place as a Pater Noster in a Synagogue.

Let’s face it, the present Knesset is full of what I would call parliamentary riffraff. Men and women I would not drink a cup of coffee with. Some of them look and behave like walking jokes. One is suspected of owning a bordello in Eastern Europe. Several would be rejected out of hand by any self-respecting private employer.

These people are now engaged in an unprecedented competition of outrageous “private” bills – bills submitted to Knesset vote not by the government, but by individual members. I have already mentioned some of these bills recently – like the bill to recognize Israel as the “National Home of the Jewish People” – and they multiply by the week. They do not attract any special attention, because the bills introduced by the government are hardly more sensible.

The question necessarily arises: how did these people get elected in the first place?

In the old parties, such as the Likud and the Zionist Camp (a.k.a. the Labor Party), there are primaries. These are internal elections, in which the party members select their representatives. For example, the head of the workers’ committee of a large public enterprise got all the employees and their families registered in the Likud, and they got him on the party list for the general elections. Now he is a minister.

Newer “parties” dispense with all this nonsense. The party founder personally selects the members of the party list, at his or her pleasure. The members are totally dependent. If they displease the leader, they are simply kicked out at the next election and replaced by more obedient lackeys.

The Israeli system allows any group of citizens to set up an election list. If they pass the electoral threshold, they enter the Knesset.

In the first few elections, the threshold was 1%. That’s how I got elected three times. Since then, the threshold has been raised and now stands at 3.25% of the valid votes.

Naturally, I was a great supporter of the original system. It has, indeed, some outstanding advantages. The Israeli public has many divisions – Jews and Arabs, Western Jews and Eastern Jews, new immigrants and old-timers, religious (of several kinds) and secular, rich and poor, and more. The system allows all of these to be represented. The prime minister and the government are elected by the Knesset. Since no party has ever achieved a majority in elections, governments are always based on coalitions, which provide some checks and balances.

At some stage, the law was changed and the Prime Minister was elected directly. The public quickly became disillusioned and the old system was reinstated.

Now, seeing the riffraff that have entered the Knesset, I am changing my opinion. Obviously, something in the existing system is extremely wrong.

Of course, there is no perfect election system. Adolf Hitler came to power in a democratic system. All kinds of odious leaders were elected democratically. Lately, Donald Trump, an unlikely candidate, was elected.

There are many different election systems in the world. They are the results of history and circumstances. Different peoples have different characters and preferences.

The British system, one of the oldest, is very conservative. No place for new parties or erratic personalities. Each district elects one member, winner takes all. Political minorities have no chance. Parliament was a club of gentlemen, and to some extent still is (if one counts gentlewomen).

The US system, much younger, is even more problematic. The constitution was written by gentlemen. They had just gotten rid of the British king, so they put in his place a quasi-king called president, who reigns supreme. Members of both houses of parliament are elected by constituencies.

Since the founders did not trust the people too much, they instituted a club of gentlemen as a kind of filter. This is called the Electoral College, and just now they elected (again) a president who did not obtain the majority of the votes.

The Germans, having learned their lesson, invented a more complicated system. Half of the members of parliament are elected in constituencies, the other half on country-wide lists. This means that the one half are directly responsible to their voters, but that political minorities also have a chance of being elected.

If I were asked to write a constitution for Israel (we have none) what would I choose? (No need for panic. According to my calculations, there is about a one trillion to one chance for this to happen.)

The main questions are:

- Will members of parliament be chosen in constituencies or by country-wide lists?

- Will the chief executive be elected by the general public or by parliament?

Each answer has its pros and cons. It is a decision about what is more important under the existing circumstances in each country.

I was very impressed by the recent elections in France. The president was elected in a direct nation-wide vote – but with an incredibly important and wise institution: the Second Round.

In a normal election, people first vote emotionally. They may be angry with somebody, and want to express their feelings. Also, they want to vote for the person they like, whatever his or her chances. So you have several winners, and the final winner may be somebody who has got only a minority of the votes.

The second round repairs all these faults. After the first round, people have time to think rationally. Among the presidential candidates who have a chance to win, who is the closest to me (or the lesser evil)? In the end, one candidate necessarily gets a majority.

The same applies to the candidates to the Assemblée Nationale, the parliament. They are elected in constituencies, but if no one gets a majority at the first try, there is a second round there, too.

This may impede the arrival of newcomers, but lo and behold – the election of Francois Macron shows that even in this system an almost complete newcomer can become president.

Sure, an expert can probably find faults in this system, too, but it seems reasonably good.

Over the years I have visited several parliaments. Most of their members left me singularly unimpressed.

No parliament is composed of philosophers. You need a lot of ambition. cunning and other unseemly traits to become a member. (Myself excluded.)

I grew up admiring the US senate. Until I visited that institution and was introduced on the floor to several members. It was a terrible disappointment, Several of them I spoke with about the Middle East obviously had no idea what they were talking about, though they were considered experts. Some were, frankly, pompous asses. (Pompous Asses are a category well represented in every parliament).

I learned that the real business of the Senate is conducted behind the scenes by the consultants and advisors of the senators, who are far more intelligent and informed, and that the role of the members themselves is to look good, collect money and make highfalutin speeches.)

TV is changing the picture (literally) everywhere.

TV cannot show party programs, so programs are obsolete. TV cannot show political parties, so parties are disappearing in many places, including Israel. TV shows faces, so the faces of individuals count. That explains why good-looking politicians in Israel create new parties and appoint the Knesset members, including the riffraff (some of them also good-looking), who would never be elected in a direct constituency vote.

When Adlai Stevenson ran for the presidency, he was told “Don’t worry, every thinking person will vote for you.”

“But I need a majority,” Stevenson famously replied.

http://zope.gush-shalom.org/home/en/channels/avnery/1495203281/

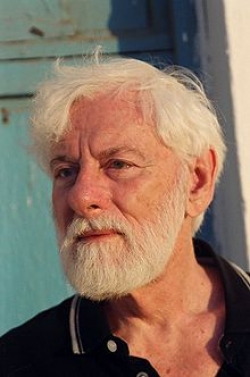

Uri Avnery is an Israeli journalist, co-founder of Gush Shalom, and a former member of the Knesset

This article first appeared on the website of Gush Shalom (Peace Bloc) – an Israeli peace organisation

Categorised in: Article

This post was written by Uri Avnery