Britain’s Neo-colonial Policies in Oil-rich Nigeria Fuel War and Malnutrition

March 17, 2019 12:00 am Leave your thoughts

The controversial re-election of Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari underscores the militarization of the country’s political system and economy. The foundations of corruption were laid by the British Empire, but ongoing poverty and counterinsurgency wars are stoked by a neo-colonial mentality that sees Nigeria-and Africa in general-in terms of their potential financial worth. For example, as Bloomberg reports that a US and British-based hedge fund is “seizing Nigerian assets,” Punch reports that a helicopter used to monitor the recent general election is being replaced with a military jet. As we shall see, Britain trains the Nigerian Air Force.

Under British rule, Nigeria was split along religious lines, with the northern politics dominated by Muslim leaders (a remnant of the country’s Islamic history) and southern politics dominated by Christians (missionaries being a weapon of European colonialism). This was called “indirect rule” because Britain established systems in which Nigerians could govern themselves but under conditions that benefited the British. Nigerians struggled for independence, which they achieved-at least formally-in 1960.

The Biafra War (1967-70) was a bloody and unsuccessful effort by secessionist movements to form an independent state. Britain supported a united Nigeria. A now-declassified memo prepared for Britain’s PM Harold Wilson in 1968 states that British investments in Nigeria were “worth up to £175 million. Our annual export trade is about £90 million. 16,000 British subjects live in Nigeria. All this would be at risk if we abandoned our policy of support for the Federal Government and others would be quick to take our place.” Later, Britain supported the north in an effort to preserve its oil interests. The UK imposed a blockade and supplied the arms to crush the Biafra independence movement. The war and famine killed around 2 million people.

After the war, and under successive military dictatorships, oil operations intensified, particularly in Ogoniland and in the Niger Delta regions. The oil companies have caused such massive environmental damage that many villagers literally live knee-deep in oil spills, as confirmed by devastating photos included in a UN report .

The oil companies have also created a negative feedback loop for themselves. Some companies allegedly contract crooks to do their dirty work. This leads to crime and gun-running.

Rival gangs compete for black market oil and weapons. But the gangs soon got out of control and threatened oil operations. The “resource curse,” as it’s called, means that massive windfall revenues from oil sales go mainly into the pockets of corrupt rulers and the oil companies, not into social programs.

Today, around 87 million Nigerians out of a population of 190m live in extreme poverty, according to the World Poverty Clock. Nigeria ranks 157 on the UN Human Development Index of 189 countries. It has the second-highest rate of childhood stunting (an effect of malnutrition), affecting 43% (or 16.5m) of the country’s children.

Nigeria’s GDP is $375bn. Only recently has the government requested $20bn in tax debt from energy companies, including Shell, Chevron, Exxon Mobil, Eni, Total and Equinor.

Since 2001, the British government has increased its military exports to and training in Nigeria, almost entirely to militarize the Niger Delta. According to a report by Campaign Against the Arms Trade and others, “Shell successfully lobbied for increased UK military aid to Nigeria.” The report directly links the decision of Britain’s then-PM Gordon Brown to increase military aid to the direct collapse of the Niger Delta ceasefire.

In addition to the gangs, the central government together with British Special Forces, have been fighting a counterterrorism war against the terrorist group, Boko Haram. But a US House of Representatives Committee report from 2011 highlights what the corporate and state media in the US and Europe choose to ignore: that as bad as Boko Haram are, their actions are a response to arguably much worse actions by the government and the oil corporations exploiting the country. To quote the intelligence report:

“A number of factors have been attributed to fueling Boko Haram’s violence and fanaticism, including a feeling of alienation from the wealthier, Christian, oil-producing, southern Nigeria, pervasive poverty, rampant government corruption, heavy-handed security measures, and the belief that relations with the West are a corrupting influence. These grievances have led to sympathy among the local Muslim population despite Boko Haram’s violent tactics.”

The reality is more nuanced than the cartoonish “good guys vs. bad guys” narrative of mainstream media. As the report notes, the authorities cracked down hard. So-called Islamic State (Daesh) saw the carnage as a way of attracting new recruits to jihad. The rise of Daesh in Nigeria gave the UK more pretexts to escalate its operations. Instead of addressing the concerns outlined in the House of Representatives report, the British and Nigerian authorities responded with more indiscriminate violence. The British House of Commons Library acknowledges that:

“President Buhari and the APC government have … been criticised (as, to be fair, were those [UK-backed] predecessors too) for failing to get to grips with the interlocking ‘root causes’ of violence – poverty, inequality, marginalisation and corruption – in Nigeria, whether in the north or elsewhere, and for often appearing to favour military responses over political ones.”

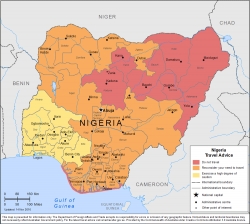

Supposedly mistaking it for a Daesh base, the British-trained and armed Nigerian Air Force even bombed an internally-displaced persons’ (IDP) camp in 2016, killing at least 50 people. The report also acknowledges that quite apart from counterterror operations, the Nigerian Army is active in 30 out of Nigeria’s 36 states, mainly quelling gang violence.

The government’s brutal crackdowns on Daesh have displaced 2 million Nigerians, pushed over 200,000 out of the country, and spilled over into neighboring states. Despite this, the UK proudly established a permanent British Military Advisory and Training Team, and sends so-called Short Term Training Teams to the Nigerian Armed Forces. In light of the revelations about the IDP camp bombing, it’s worth reiterating that the UK has been training the Nigerian Air Force since 2015. In August 2018, the UK and Nigeria signed a so-called defense and security partnership agreement in the capital, Abuja. The UK aims to train a staggering 30,000 troops.

While alternative researchers are right to raise the issue of media silence over Britain’s involvement in the war against Yemen, we must not forget the UK’s centuries-old interference in resource-rich Nigeria, one that today is fueling gang violence, the indiscriminate targeting of civilians by military forces in a so-called counterterrorism war, the enablement of giant oil companies to deplete precious reserves, and the malnutrition of the country’s young and most vulnerable.

Dr. T.J. Coles is an associate researcher at the Organisation for Propaganda Studies and the author of several books, including Britain’s Secret Wars (Clairview Books).

Categorised in: Article

This post was written by TJ Coles