Coal Rush!

October 23, 2022 4:00 pm Leave your thoughtsArticle by Mark Horner

A big surprise, albeit politically muted, is the EU’s rush back to brown or thermal brown coal (“coal”). The rush started early in 2021, a year before the EU sanctioned Russian energy, and is couched in a pivot from gas-to-coal.

The pivot runs counter to the EU’s Environmental, Social and Governance (“ESG”) policy which is anti-coal and so warrants investigation.

The EU’s consumption of coal

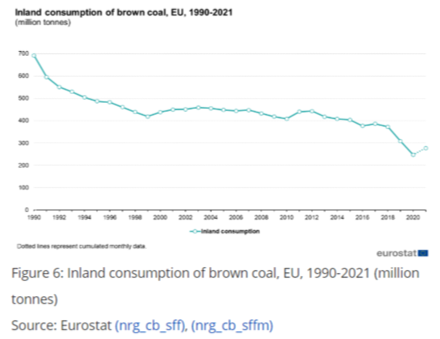

From 1990 to 2020, the EU materially reduced its consumption of coal. The following chart shows that “in the 1990s, the consumption [of brown or thermal coal] decreased rapidly, broadly stagnating between 2000 and 2015 … [and from] 2018 to early 2020, consumption of brown coal decreased sharply”. (Eurostat, 2 May 2022).

The pivot

Paradoxically, the EU’s pivot from gas-to-coal started before the COP 26 Conference (the United Nations Climate Change Conference, #26) held in 2021, and at the conference the EU agreed to “phase out” coal at a time when it was increasing consumption.

As it turns out the EU’s pivot was made reluctantly, as a last-resort, and triggered by shortages of gas. Yet, ironically, the gas shortages were in turn triggered by escalating pressure applied to financiers, investors and organizations to adopt ESG policies and dump fossil energy.

Yet, a question on the mind of environmentalists is: given an energy gap then why did the EU rush to coal and not rush to speed up its transition to renewable energy?

Its a good question and the answer goes to energy security. We all know that renewable energy is volatile, it relies on the vagaries of nature and that inherent insecurity when not backed up by the security of fossil or nuclear energy puts the big consumers of electricity at big risk. And there are no bigger consumers in the EU put at risk by relying on the vagaries of nature than those that make up the EU’s industrial heartland, e.g., Germany and Poland.

The chart, below, shows that the rush to coal is primarily driven by six of the 27 member states. Their main source of energy security rests on burning gas and coal to produce electricity so as to power their industries. And when there is a shortage of gas, like now, they fill the gap by burning more coal.

The size of the pivot

The size of the pivot to coal is not minor, although it looks small on the charts, above. The EU increased its consumption by 14% in 2021 and in 2022 its increase is trending at 7% (IEA Press Release, ‘Global coal demand is set to return to its all-time high in 2022‘, 28 July 2022, page 2). And the pivot will likely roll on for years to come as the EU’s sanctions on Russian energy filter through and threaten to de-industrialize the EU’s industrial heartland.

Putting the EU’s coal rush into perspective, it is not confined to Europe: the IEA is expecting that global consumption of coal in 2022, subject to China’s recovery, will reach the record level set in 2013 (ibid, page 1).

Is renewable energy a fallen-hero?

With respect to renewable energy there is a disconnect between the evangelistic narratives of Western governments, mainstream media and academia, and reality.

The reality is that the success of renewable energy, thus far, is due to successfully picking ‘low hanging fruit’ primarily by filling residential electricity grids. The rush and pivot to coal suggests that renewable energy is not yet mature enough to pick the ‘high hanging fruit’ by securely supplying the EU’s risk-adverse industrial heartland.

The sources of renewable energy which will likely provide that security are nuclear and green-hydrogen. Yet, each has well-known social, political and economic hurdles to overcome. And additionally, green-hydrogen faces non-trivial technical hurdles.

The Renewable Energy Magazine states that the technical hurdles facing green-hydrogen include: scalability, devising low-carbon production methods, transportation and storage. And it is timely to add that as at June 2021: “98 percent of hydrogen is made from fossil fuels with no CO2 emissions control”, Columbia Sipa Center on Global Energy Policy.

Renewable energy is still a hero, however for it to retain or grow its hero status over the long-term communities will have to accept nuclear energy plants – and many will not – and/or the technologists will have to overcome the hurdles facing green-hydrogen.

The future of coal

With gas in short supply solar, wind and hydro energy subject to the vagaries of nature, nuclear and green-hydrogen facing hurdles, then coal, by default, has a future albeit in a marriage-of-necessity.

Coal and High-Energy-Low-Emission (“HELE”) power plants fitted with Carbon-Capture-Storage (“CCS”) technology (“HELE+CCS”) combine to generate low-emission electricity, and once the combination was considered part of the future. And yet it might transform a marriage-of-necessity in to a marriage-of-convenience.

A marriage-of-convenience

In 2012, the IEA produced a HELE roadmap (‘Technology Roadmap – High-Efficiency, Low-Emissions Coal-Fired Power Generation‘) and explained that HELE+CCS power plants can reduce CO2 emissions by about 80%-90% (page 19). And that is materially more than the halving of emissions required to meet the ‘2C-3C global warming’ target (page 1).

Note: the ‘2C-3C global warming’ target was a preliminary target (in 2012) and the Paris Agreement settled (in 2015) on a “well-below 2C” or “preferably” a ‘1.5C global warming’ target. Nevertheless, the case for including HELE+CCS in the transition still stands.

In Europe, it is estimated that there are about 137bn tonnes of brown and black coal (BP, ‘Statistical Review of World Energy 2021‘, page 46). And which is currently valued at about US$55tn or the equivalent of 14 times Germany’s GDP.

In the ground, the coal has no value. However, if used in HELE+CCS power plants it has substantial value: it more than meets the emissions reduction requirement and provides the EU with the twin benefits of self-sufficiency and security over electricity supply.

And in the meantime, this marriage-of-convenience would provide the EU with the time and funds necessary to grapple with the hurdles facing nuclear and green-hydrogen.

Categorised in: Uncategorized

This post was written by LPJAdmin