Hans Modrow – Obituary

February 22, 2023 9:11 pm Leave your thoughtsArticle by John Green

Hans Modrow, the last prime minister of the GDR before free elections took place in March 1990, died aged 95 on 11 February. Modrow was born in 1928, and left school in 1942. He was conscripted into Hitler’s Volkssturm as a 17-year-old and despatched to the Russian front. He was one of thousands of soldiers to be captured by the Red Army and was sent to a POW camp near Moscow where he joined an anti-fascist school set up by the Red Army. On his release in 1949 he was determined to help build a new, democratic, and anti-fascist Germany.

He first returned to his former career as a machine tool fitter, and there became politically active in the GDR’s socialist youth movement. He rose through the ranks of the ruling Socialist Unity Party, and in 1973, became its regional secretary in Dresden. There, he won widespread respect for his honesty and modest lifestyle.

He was a popular figure in the Party and widely admired for his tolerance, innovative approach, and lack of dogmatism. He was one of the few leaders who publicly criticised longtime SED general secretary Erich Honecker.

From 1989 onwards, peaceful demonstrations by GDR citizens demanding change began in various towns, including Dresden, Modrow immediately sought to defuse what could have become violent confrontations and promoted dialogue between the demonstrators, the authorities, and the church.

Even before these events he had realised that the party and government needed radical reform and had to involve the people more in government if socialism in the GDR were to survive. His criticism of the GDR leadership led some in the West to dub him the ‘East German Gorbachev’ – not a sobriquet he would have approved of – he later had strong disagreements with Gorbachev. Already, as early as 1987, Gorbachev and the Soviet KGB had even looked at the possibility of Modrow replacing party secretary, Honecker who was implacably hostile to Perestroika.

By the late 80s, with the SED and government in the GDR collapsing as a result of the widespread protests, Modrow was seen as a unifying figure. He became prime minister in 1989, four days after the Wall was opened in a panic reaction by the previous government.

Modrow’s prime concern at this time was to prevent the situation becoming uncontrollable. He worked tirelessly to ensure that the transformation would be peaceful and carried out in such a way that daily life would not be threatened. He, alongside a number of leading comrades hoped to be able to salvage the achievements of socialism before the steamroller might of West Germany crushed them all. Despite Herculean efforts, they were unable to achieve this – events moved too rapidly. The situation was made worse by Gorbachev’s high-handed political manoeuvring on the international stage. He ignored the concerns of Modrow and his GDR comrades and over their heads came to an agreement

with BRD Chancellor Helmuth Kohl which gave the green light for the consequent takeover. Modrow had been keen to avoid an over-rapid unification process fearing such a take-over by the much stronger Federal Republic, arguing instead for a gradual merging of two different systems. He preferred the idea of a confederation of the two states.

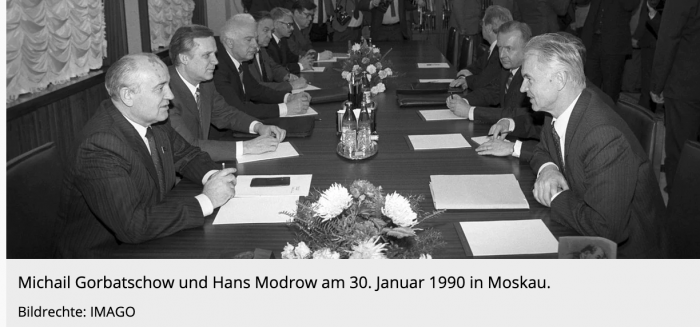

In January 1990, Gorbachev and Modrow met in Moscow to discuss the future of the GDR. Modrow proposed the establishment of a neutral Germany, an idea the West Germans rejected. Kohl wanted to push through unification as fast as possible, to be seen as ‘the man who reunited Germany’. He realised that Gorbachev could be more easily manipulated than Modrow. Modrow gives us the details of this process in his book Perestroika and Germany: The Truth Behind the Myths.

During his short time in office (until 15 April 1990) Modrow set up up a ‘Round Table’, a grassroots governing body that drew in all significant political forces in the GDR. Amongst other things, the Round Table drafted a completely new constitution for a united Germany which was, however, again rejected by Kohl.

After unification, he served first as a member of the Bundestag and later as an MEP, 1999-2004. He was made honorary Chair of Die Linke (The Left party) and remained an active participant in the political life of Germany until his death.

Because he remained a staunch socialist, he was snubbed by the political elite of the Federal Republic. In 1993, in an attempt to criminalise him, he was convicted in a Federal court of ‘electoral fraud’ during his time as regional secretary in Dresden.

In his later years he was often consulted by other countries, wishing to learn about the process of uniting a divided country and how to build bridges. In this role, he travelled to South Korea, Cuba, China and other countries.

In his last book, Building Bridges, he covered this subject in the form of personal reminiscences on the ongoing relations between the GDR and Chinese comrades which continued even after the demise of the GDR.

So, what was his legacy? Although so much of what he tried to do to protect the achievements of 40 years of state socialism, was unsuccessful, one thing he did manage was to introduce a law, today called the ‘Modrow Law’ which protected GDR homes from the brutal impact of Western property vultures: It allowed asset-poor Easterners to buy the land on which their houses stood for amounts far below the market price. In his later years, when leaving his flat on East Berlin’s Karl Marx Allee or taking public transport, he would be regularly stopped by grateful citizens for a friendly chat or warm greeting. For many former GDR citizens, he was undoubtedly held in high esteem.

Categorised in: Uncategorized

This post was written by LPJAdmin