Zimbabwe: Why the International Community Must Intervene

December 12, 2008 12:00 am Leave your thoughts The views expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not represent the views of London Progressive Journal.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not represent the views of London Progressive Journal.

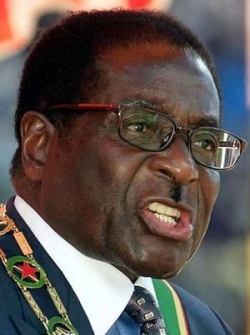

Zimbabwe, piloted by Robert Mugabe, has travelled back in time. Once one of the most prosperous countries in Africa and a magnet for economic migrants from all over the continent, it now faces a cholera epidemic, the staggering devaluation of its currency, political oppression and violence. Leaders in Africa and beyond are calling for help, and in some cases even outside intervention – even the African Union has called for him to surrender his grip on power. What form an intervention would take is, however, unclear. What kinds of international laws and customs allow States to intervene, and how do these same laws and customs restrain them?

When it comes to Africa, the international community is paralysed by experiences of the last decade. We do not want another Rwanda – to sit idly by while genocide occurs – and yet action in response to Sudan has been slow and indecisive, hampered in part by disagreements in the UN Security Council. There is a thin line to walk when it comes to weighing up intervention in Zimbabwe. Mugabe is not directly threatening his neighbours or anyone else, but his policies are having a devastating impact on his people and the region. The Rwandan genocide looked like a sudden explosion from where we were sitting, but the seeds had been planted decades earlier, with tensions simmering and finally reaching boiling point with Hutu militia massacring Tutsis by the hundreds of thousands. The West was slow to react, and this paralysis was a crippling blow to the new world optimism of the 1990s.

In Zimbabwe, it looks like the cholera outbreak may be the final straw in a recent plunge into chaos, and yet Mugabe has been politically ruthless for decades. He has systematically eliminated his opponents and masterminded campaigns of intimidation, leaving him king of the castle and the only ruler since independence. The oppression of his people began many years ago, and the disastrous land reform over the last decade has taken food from everybody’s mouths, relying heavily on a rhetoric of anti-colonialism that he still uses today. Now the time has come that even his friends and neighbours at the table will no longer let him use it. Mugabe’s grip on power borders on the psychotic, and until now nobody has tried to make him leave. South Africa’s Thabo Mbeki has failed, treating Mugabe like an eccentric uncle he wished not to offend by suggesting it may be time to put down his wine glass and leave the party. But how much can the international community, and his neighbours, actually do?

Humanitarian intervention in international theory

Humanitarian law is for the most part concerned with the law of combat and the treatment of victims. Its legal roots are in the Hague and Geneva Conventions, which make provisions for, among other things, the humane treatment of prisoners. Humanitarian intervention is an offshoot of this set of laws and customs, and is defined as “the threat or use of force across state borders by a state (or group of states) aimed at preventing or ending widespread and grave violations of the fundamental human rights of individuals other than its own citizens, without the permission of the state within whose territory force is applied”.

Humanitarian intervention lies on the fault lines of a central debate in international relations, trying to balance the promotion of human rights and the rights to life with the seemingly opposing ideal of State sovereignty, the basic building block of the international system. So how far is intervention a legitimate exception to the supremacy of sovereignty? The two corners of the debate in international theory are the solidarist and the pluralist views of intervention. Pluralists maintain that sovereignty should preclude any intervention from other states, with solidarists arguing that sovereignty can and should be subsumed under the interests of human rights – indeed that it is our duty to intervene to reduce suffering.

After Rwanda, the international community had tacitly agreed not to repeat the experience and to adopt a more solidarist approach, to promote the moral duty to protect and uphold human rights and intervene in those states that fail to protect these rights. This has been commonly evoked since the end of the Cold War: intervention in a State that has violated the human rights of its citizens – not only on moral grounds but also on the grounds that such undermine regional security and, by extension, the international community. But this policy has always been checked by political interests. Under the human rights argument, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had apparent justification. However, the US case for intervention may have been more convincing if their targeting of human rights violations were not so laughably selective. The invasion of Iraq has been widely condemned as illegal under international law, as it was done without UN authorisation. The selective blind spots States have in dealing with human rights violations in one country while turning a blind eye to others, sometimes for sound regions like global stability, has made the practice of humanitarian intervention seem like organised hypocrisy.

In international relations, the system of states has its own logic, governed by national interests. This may be a bitter pill to swallow given all the international efforts to the contrary, but it is logical for states to look after their own interests. One must also remember that, until fairly recently, countries did not have to explain to others why they wished to protect their interests or how. International institutions only have as much power as States give them – like fairies, they may cease to exist if States stop believing in them. The building-block of the international system is sovereignty as defined by the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. As such it is the responsibility of the State to be a benign provider for its citizens. The theory and practice of international society is centred on the struggle of moving beyond national interests to international ones, and the obstacles which stand in the way. Because a government’s first responsibility is to its own citizens (if only for its own political survival) this is the major motivation for States’ behaviour. By the same token, a State that has so clearly failed its citizens loses its legitimacy to govern – in theory this failure should allow the international system to intervene. It is precisely this fact that is so difficult to reconcile with the concept of sovereignty. It is the role of international institutions to get States to act in the interests of the international community as well as its own, or at least find situations where national and international interests dovetail. Consensus is needed to confer legitimacy on intervention. It is precisely the unilateral nature of US intervention which has made a mockery of the attempt to act in consensus.

The US’s unilateral moves over the past decade are unusual for our time, but much more in keeping with the way political history has played out. Human rights, international law, and the United Nations are part of the attempt to make the international system more benign – but these are also rightly still seen by many in the developing world as a continuation of Western politics by other mean,s because the application of these norms has been patchy and selective. This brings us back to intervention and the African continent.

How can we intervene?

Under the new concept of an international “responsibility to protect” (the ‘R2P’) adopted unanimously by world leaders (including Mugabe) at a UN world summit in New York in 2005, intervention in a state’s internal affairs is permitted in the event of genocide, crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing and other mass atrocities, if that state is unwilling or unable to protect its own people. This responsibility places an actual obligation on governments, usually acting through international bodies such as the UN, to intervene in such cases.

Conventional criticism accuses other States of not doing anything because they do not have strategic interests in Zimbabwe. But Zimbabwe has abundant national resources, more than enough to give the country and the region the economic prosperity it once had.

A major argument for intervention in this case, notwithstanding the situation on the ground, is the fact that his people actually voted him out (if only by too small a margin to make it stick). Another is that the chorus of leaders calling for his end includes his erstwhile allies, and not just “Western colonialists”. As such the international community, should they act, has the blessing of neighbours which in the past may have rallied around Mugabe. A UN intervention would probably receive the support of Zimbabwe’s neighbours, which should be enough to tip the scale in favour of acting. Kenya’s president, The African Union, and African National Congress leader Jacob Zuma, have called for Mugabe to step down and called for foreign intervention if he does not resign. The African Union (AU) was the only organisation, until September 2005, with a mandate to intervene in member-states where “grave circumstances” are taking place. The AU Constitutive Act defines “grave circumstances” as “war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity.” The AU is somewhat constrained however in the wording of its mandate. It can intervene on two grounds: when a state has collapsed and its citizens’ livelihoods are gravely threatened or when invited by a state that is too weak to protect the livelihoods of its people.

An internationally-sanctioned intervention could be made under the UN mandate by invoking Chapter VII (which deals with threats to peace) of the UN Charter, as well as R2P. All the criteria for such an intervention are met in Zimbabwe. It has lost its sovereignty by failing to protect its civilians from loss of lives and livelihoods and all peaceful efforts to end the suffering of the Zimbabwean people seem to have been exhausted. Mugabe tried to hijack the last elections, and this is not even taking into account his cumulative political crimes since, and before, independence in 1980. The humanitarian and economic crises in Zimbabwe are directly linked to Mugabe’s disastrous policies. His policies have led to massive violence and death, displacements of people, damages to social and economic systems, acute food shortages, and overall threats to the livelihoods of the Zimbabwean people.

What now?

Any intervention involving sanctions or armed force requires authorisation by the UN Security Council, meaning that were would have to be no opposition from any of the council’s five permanent veto-wielding members: Britain, China, France, Russia and the United States. The council has issued a statement condemning the violence and intimidation surrounding the last presidential elections, but the distance from there to making a resolution or sending in troops looks daunting.

Force will have to be used as a last resort, as long as it is proportional, and may lead to a restoration of human security in the country. The AU must legitimise such an intervention. However, it would be reluctant to set such a precedent, and could insist on applying the cliché of “African solutions to African problems.”

Perhaps the answer lies within Zimbabwe – some have argued that it is for Zimbabweans themselves to topple Mugabe. If people can hardly feed themselves and are afraid of the repercussions of rising up (and were too afraid not to vote for him), it is unlikely that they will manage to change anything themselves.

There should be a Security Council resolution soon – if Zimbabwe turns into another Rwanda the R2P will have been useless, and it will harm future efforts for a more uniform policy of humanitarian intervention. It may be time for consistency.

Categorised in: Article

This post was written by Alexa Van Sickle