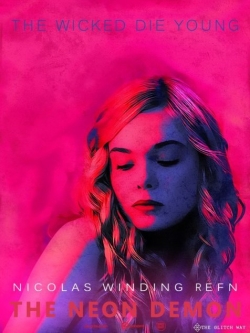

The Neon Demon – a cult classic in the making

July 16, 2016 12:00 am Leave your thoughts

Breaking taboos is the big yawn of our modern commerce dominated culture so I hesitate to recommend a movie that seems, superficially at least, to be gratuitously designed to break as many taboos as is conceivably possible within the confines of its two hour duration. But while it may not be for the squeamish or the easily offended, there is actually hardly any nudity and very little sex in this saga of a young girl’s search for fame and fortune in the ruthless fashion industry of LA. The topics of necrophilia and cannibalism that crop up in the course of the story are perhaps about as taboo-breaking as you can get these days. But to quote the late Kenny Everett, surprisingly, it is all done “in the best possible taste”.

Visually Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn’s film is absolutely stunning and sumptuous, while the dialogue has all the epigrammatic qualities that one associates with Wilde. Indeed, the screenplay is quite Pinteresque in its deliberate choice of words to create maximum impact which effortlessly enables it to construct a sinister atmosphere that pervades the film from its very first scene.

In terms of the mood, the colour scheme of shades of purple, blue and red, combined with the setting and the character types, we are lodged firmly in the world of David Lynch. It is that dark hinterland on the edge of the city where the innocent ventures only to become corrupted if not annihilated. It is a case of Blue Velvet meets Mulholland Drive.

The glamorous world of the fashion industry has its dirty underside. It is a world where male photographers literally call all the shots and are free to prey on the young models, who know they must remain always passively compliant if they want to make a lot of money out of their prettiness. As the heroine believes, she has no talent, apart from her prettiness.

Played by newcomer Elle Fanning, who looks like a young Cara Delevingne, Jesse is a naive 16 year old orphan who pretends to be three years older to get a job, convincing no-one but allowed to work all the same. “People will believe whatever they are told,” her agent comments.

It is the traditional theme of virtue in peril, but there is no triumph over adversity at the end. Staying in a cheap motel, Jesse finds herself in Psycho territory complete with the predatory motel manager who betrays the tendencies of a paedophile and who we are led to believe sexually assaults a resident in an adjourning room. When what appear to be screams for help next door, the heroine takes flight only to find herself in a far more dangerous place where she ultimately meets her death by falling into an empty pool, which slow begins to fill with her blood as she lies writhing in agony.

It is a grim, uncompromising ending, the death of the heroine, who begins as an embodiment of goodness only to become gradually corrupted as she quickly learns how to hustle in the cynical world. It is shocking like the ending of Samuel Richardson’s 18th century novel, Clarissa, where the heroine dies struggling to preserve her virtue intact after an ordeal unfolding over several thousand pages.

Jesse realises that she no longer wants to be like older models, who are already well past their sell by date when they reach their mid-twenties; in truth, it is they who want to be her, because of her natural beauty and the unblemished innocence that they will never again be able to recapture.

This is all very reminiscent of David Lynch and it is surprising how few reviewers seem to have made this connection.

When asked how she dealt with a rival who stole an assignment from her, one of the older models nonchalantly replies with the words, “I ate her”. Having just witnessed the ugly death of the young heroine in the previous scene, one suspects that her reply isn’t mere hyperbole. And so it proves. In the very next scene one of the models vomits up the heroine’s eye ball only for her friend to immediately pick it up and devour it herself. All very symbolic of a dog eat dog world and it makes the severed ear at the start of Blue Velvet appear rather tame.

The Neon Demon is a cautionary tale, a visual feast and a disturbing examination of a profession whose reality is actually far more disturbing in its ruthlessness than the fiction presented on screen. One recalls the stories recounted by former super models of the molesting and sexual assaults they felt compelled to endure at least until they became famous. The film is a bold statement about the total callousness and inhumanity of an industry of which the media and popular culture are totally obsessed. The stark ending has its necessary shock value to awaken us out of our complacency that we can allow such vile exploitation of teenage girls for male gratification to carry on and do nothing about it. As such it is a necessary movie and something of a flawed masterpiece. It not to everyone’s taste; indeed, on the day that I saw it, the cinema emptied well before the end credits started to roll.

I don’t imagine much popcorn was consumed on that occasion too. Clearly, it does not make for easy viewing. Nevertheless, it has all the hallmarks that will ensure it is destined to become a cult classic.

Tags: ArtsCategorised in: Article

This post was written by David Morgan